Global Sport Matters: The Sports Media Issue (Part II)

Women making progress, covering sports when it doesn't stick to sports, the benefits of Black journalists covering Black athletes, the case for locker room access, and disparities in doping stories.

Welcome to Hreal Sports, a newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. Sign up and tell your friends!

Welcome back! I’m delighted to (very belatedly) share the second set of stories for the July issue of Global Sport Matters, the digital publication of the Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University. For those of you who are unfamiliar with our work, we cover a wide range of outside the lines, sports and society topics though original research and reporting, and via podcasts, live events, standalone articles, and monthly themed issues.

Our July issue is devoted to the influence of sports media. Perhaps it’s a bit meta—and more than a bit self-flattering!—to say this, but how sports are covered plays a major role in how the public perceives them. That’s true for evaluating performances on the field of play, and even more true for off-field issues ranging from health and safety to labor rights to gender and race. So as sports media evolves and digital outlets and platforms become as or more popular and important than traditional print, radio, and television sources of coverage, what does that mean for how we think about sports?

Our issue attempts to answer this question. Links and summaries are below for stories on how women are making progress in a traditionally sexist field, the tricky territory of covering sports when it doesn't stick to sports, the benefits of Black journalists covering Black athletes, the case for locker room access (farts and all!), and disparities between doping reporting about the U.S. and Russia. Hope you enjoy—and if you missed Part I, just click here.

“'Every Day Gets Better': The Rise of Women in Sports Media,” by Anna Katherine Clemmons.

Progress is not linear and not often quick, but through interviews across multiple generations of sports journalists in the 21st century, we can see that women in sports media have more opportunities and face less prejudice than they did in previous eras.

In Jacksonville, I was waiting in the Jaguars’ locker room to individually interview several players after practice, during the team’s lunch session. The Jaguars’ media relations staff was pulling aside each player and sending them into the room, letting them know that they’d be speaking to a reporter.

I wore a green, knee-length skirt and a black shirt with a high neckline. Though I was a young, relatively new reporter, I had learned to dress comfortably yet conservatively, as a reminder that I was there in a strictly professional capacity. I had set up two folding chairs along the back wall for myself and each interviewee.

My first interviewee, a 300-plus pound lineman, walked in and saw me sitting in a chair, recorder in hand. I waved and said hello. He then walked over to a massage table, took his shirt off, laid down, put his face in the donut hole of the table, and said, “Let’s do this!”

I was momentarily confused. Then I realized: he thought I was a massage therapist. Nothing about my outfit or my demeanor would have given him that impression. It was simply because I was a woman.

Yes, that moment happened 16 years ago, and the lineman clearly meant no harm.In fact, when I informed him I was with ESPN The Magazine, he quickly sat up, face red, and apologized. Yet, I wondered: would this have happened to a male reporter?

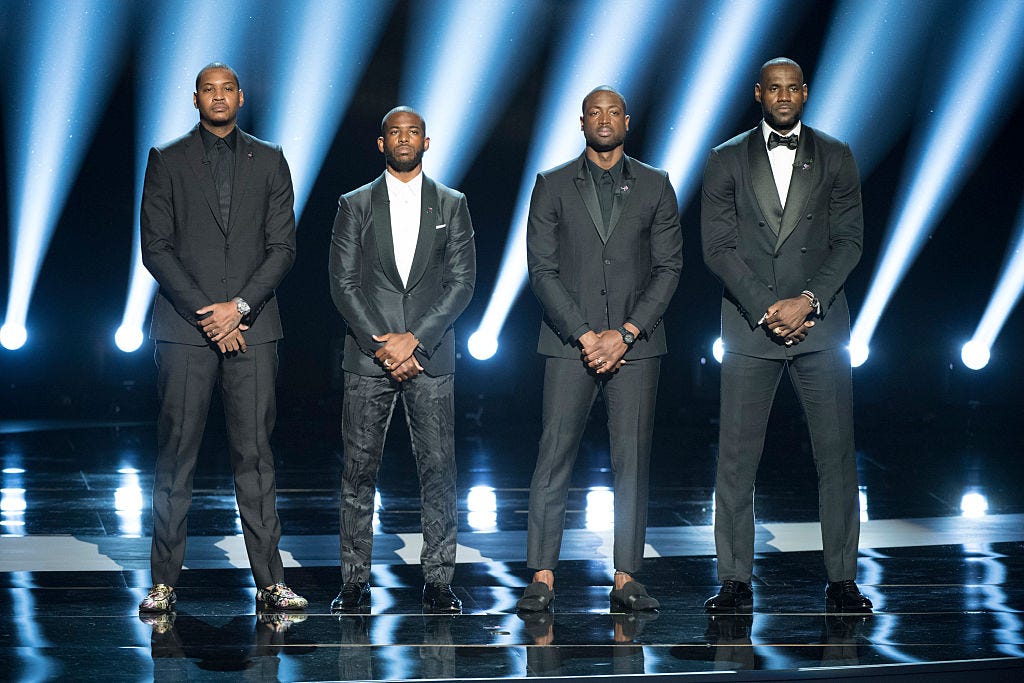

“When The Sports World Won’t Stick to Sports, What Does That Mean For Sports Journalism?” by Matt Crossman.

As athletes become wealthier and more outspoken and sport continues to be a site for political and social discourse, it's impossible for sports reporters to stay in one lane.

Today, barely a week goes by without a major sports story that has nothing to do with final scores or on-field performance. From Kaepernick and other athletes kneeling during the national anthem in protest of police brutality to U.S. Women’s National Soccer team players demanding equal pay to Golden State Warriors coach Steve Kerr’s impassioned speech after the recent school shooting in Uvalde, Texas, to quarterback Aaron Rodgers’ stance on COVID-19 vaccination, social and political issues crossing over onto the sports pages has become the new normal.

Even the phrase “stick to sports” is having a moment. At least four current and former podcasts and one show on Vice TV (co-hosted by Hill, which aired in 2020 and 2021) have had a form of it in the title. Several journalists use it in Twitter bios – albeit in the negative: “I don’t stick to sports” – like a vampire slayer holding a crucifix to ward off battles before they start. I emailed Trenni Kusnierek, a two-time Emmy winner who covers Boston sports for NBC, to ask if having “No, I will not stick to sports” in her bio means people stop telling her to do just that.

Her answer: No.

“There will always be a section of sports fans,” she wrote, “who still see sporting events as their escape from the world and want all of us to shut up and ‘stick to sports’ for their own personal comfort.”

The sports world isn’t sticking to sports. Perhaps unsurprisingly, sports journalists aren’t, either. But they are catching flack for it. So how are they coping with criticism? Is it affecting their coverage? Should it affect their coverage? Is any of that criticism fair? Is it right?

“Fighting for a Voice: Why Black Reporters Covering Black Athletes Makes for Better Journalism,” by Shalise Manza Young.

American media demographics still do not represent the makeup of the country, let alone the largely Black U.S. sports leagues. This dynamic means Black athletes' stories can be lost in translation or even outright challenged by those who report the news.

After a road win against the Boston Red Sox in 2017, Baltimore Orioles All-Star center fielder Adam Jones told a USA Today reporter that one of the fans at Fenway Park had thrown a bag of peanuts at him and that he’d been called the n-word “a handful of times” during the baseball game.

Jones’ revelation, which was confirmed by Red Sox officials, was dispiriting but, unfortunately, not surprising. It wasn’t the first time Jones had heard racist taunts in Boston, and he wasn’t the only Black player to report experiencing such abuse at Fenway – even Black members of the Red Sox said they’d had it hurled at them while playing in their home ballpark.

Also dispiriting but not surprising: the reaction from some of Boston’s most visible sports media members.

Radio hosts Kirk Minihane and Gerry Callahan of WEEI, two White men, immediately cast doubt on Jones’ assertion that he’d been called the slur, even after Red Sox president Sam Kennedy appeared on the station to support Jones and say officials knew who the offending fan was. WEEI’s morning show had long established itself as a place where racist and sexist discourse was acceptable; in 2003, Callahan and his co-host at the time compared a Black high school student to an escaped gorilla, and in 2014, a Minihane rant about Fox sideline reporter Erin Andrews included calling her a “gutless b****.”

Albert Breer, a White man and suburban Boston native who covers the NFL for Sports Illustrated, suggested on Twitter that Jones should provide proof of what was said to him. Breer estimated that he had been to roughly 200 games at Fenway Park and had never heard a slur used. He subsequently tweeted that he “wasn’t doubting” Jones but that he “wanted more information” because he considered the use of the n-word a “very unusual occurrence” at Fenway.

If Jones had been covered by a group of reporters who looked liked him – and perhaps had experienced racial insensitivity in Boston themselves – then maybe he would have received more benefit of the doubt. Only that couldn’t have happened. There are two sports radio stations in Boston; in May 2017, there were a combined 17 primary hosts on those stations. All were men; sixteen were White. The picture was similar in the sports departments of the area’s two biggest newspapers, The Boston Globe and the Boston Herald, which between them had one Black columnist.

“Passing Gas, Building Bridges: Why Sports Journalism is Stronger and Better With Locker Room Access,” by Ray Glier.

Stadium capacity and sideline masks aren't the only changes sport underwent during the pandemic. Reporters were largely boxed out of normal access to teams, making it harder to tell stories and bring fans closer to the athletes they support.

Athletes are seemingly superhuman on the field. But off the field? They’re simply human, like you and me. You better believe that they speak more freely with one reporter than with 30, that they relax more when not sitting in front of a podium facing a sea of bright lights and cameras and reporters gathered for the inquisition-like experience of a press conference.

You also better believe that athletes are much more likely to offer insight to a face they trust, because they see you up close and personal, day after day. Locker rooms are where athletes and journalists get to know each other, where friendly small talk builds relationships over time, where that comfort leads to the sharing of anecdotes and stories that otherwise might never reach the wider world. They are where reporters can observe and connect with subjects at their most honest and least guarded – especially after games, when memories and emotions are particularly vivid.

As Christopher Gasper of the Boston Globe recently put it, locker rooms are where “the real work of sports journalism is conducted.” And Zoom interviews are no substitute.

Are athletes always happy with open locker rooms? Of course not. Sometimes, they don’t want to talk. Sometimes, they just want to get dressed without being asked about the shot that they missed or the ball that they dropped.

Still, there are plenty of people in sports who understand why access matters. New Orleans Pelicans guard C.J. McCollum, a journalism major in college, believes “the only way to really kind of maintain certain relationships is to have that locker room access.” Cincinnati Reds first baseman Joey Votto says that access is necessary because “media is the bridge that connects the athlete with the public and without that close proximity, I don't personally think you get that human component.” Some teams realize that reporters covering games without access can lessen the quality, depth, and objectivity of the stories produced.

“How Doping Coverage Explains Sports Journalism in the United States and Russia,” by Sada Reed.

International competition sees countries pitted against one another, which is why any cheating is treated with incredible seriousness. But a new study shows how journalists shape beliefs on "doping" with their words and framing techniques, often reinforcing tropes about why and how athletes dope.

The use of prohibited performance-enhancing drugs, or PEDs, by athletes is nothing new.

In the ancient Olympic Games, athletes “doped” with mushrooms, alcohol, and bulls’ blood and testicles. By the 19th century, competitors migrated to other substances, such as caffeine, nitroglycerine, and opium. When Danish cyclist Knud Enemark Jensen died during the 1960 Summer Olympics after allegedly using Roniacol, a medicine used to improve blood circulation, waves of Olympians publicly came forward, acknowledging that PED use was commonplace in numerous sports. The International Olympic Committee introduced drug tests at the 1968 Winter Olympics, and the World Anti-Doping Agency was created in 1999 on the heels of the Festina Affair cycling scandal to govern worldwide oversight of doping in sport.

Today, athletes in sports ranging from baseball to track and field continue to dope and anti-doping efforts continue to attempt to catch and stop them. When those efforts succeed, scandals ensue, attracting media attention and coverage.

How, exactly, those scandals are covered varies by country. And those differences have potential consequences for how fans and sports policymakers alike think about doping, as well as how to address it.

This has been Hreal Sports, a newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. If you have any questions or feedback, contact me at my website, www.patrickhruby.net. And if you enjoyed this, please sign up and share with your friends.