Global Sport Matters: The Sports Media Issue (Part I)

How Deadspin changed journalism, the stats gender gap, women athletes mastering social media, improving coverage of gendered violence, the case for "athlete apologists," and sports talk radio eternal.

Welcome to Hreal Sports, a newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. Sign up and tell your friends!

Welcome back! I’m delighted to (very belatedly) share the first batch of stories for the July issue of Global Sport Matters, the digital publication of the Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University. For those of you who are unfamiliar with our work, we cover a wide range of outside the lines, sports and society topics though original research and reporting, and via podcasts, live events, standalone articles, and monthly themed issues.

Our July issue is devoted to the influence of sports media. Perhaps it’s a bit meta—and more than a bit self-flattering!—to say this, but how sports are covered plays a major role in how the public perceives them. That’s true for evaluating performances on the field of play, and even more true for off-field issues ranging from health and safety to labor rights to gender and race. So as sports media evolves and digital outlets and platforms become as or more popular and important than traditional print, radio, and television sources of coverage, what does that mean for how we think about sports?

Our issue attempts to answer this question. Links and summaries are below for stories on how Deadspin changed journalism, the sports stats gender gap, how women athletes are mastering social media for power as well as profit, why coverage of gendered violence in sports is improving, the case for "athlete apologist" journalists, and the enduring appeal of sports talk radio. Hope you enjoy—and stay tuned for Part II!

“‘We Were Consciously Fashioning An Alternative’: How Deadspin Changed Sports Journalism,” by Noah Frank.

Deadspin blew up the tropes and traditions of old-school sports media, changing the industry by challenging the accepted narrative and aggressively pursuing stories that gave readers a peek behind the curtain at the sports elite. (Also, this story is just plain fun, and you really should read it!)

From inside professional sports front offices, Deadspin appeared at first as a curiosity.

“We started to read it and pay attention to it because it was irreverent and funny,” said Patrick Wixted, who worked in public relations with the now-Washington Commanders from 2000 to 2008. “But then it definitely became clear that if Deadspin was doing a story about you, your players or your team, or someone was reaching out to you in a PR capacity, it wasn’t going to be a good thing. Your day just took a turn.”

Wixted had moved on before some of the Washington franchise’s more egregious, latter-day scandals made headlines. But he recalls the sea change in the team’s boardroom when executives began to realize that the old ways of operating weren’t going to cut it anymore.

“Deadspin was a wake-up call to the evolution of sports media from traditional to non-traditional,” said Wixted. “It kind of signaled that time and era, that you need to be ready for it, deal with it, have a plan for it.”

Some of that shift was due to the new editorial direction at Deadspin. Both Craggs and Marchman had cut their teeth at local alternative weekly magazines (or “alt weeklies”), which certainly informed both the tone and the content of that era of the site. And while that background may have informed their approach, as internet culture evolved and twisted in the social media era, the daily content took on a novel form: It mirrored the way people consumed the Internet.

Consecutive posts could include a wild highlight from a game the prior night; an underexplored, ranked list; a 4,000-word investigative story; and a Bear (yes, a literal bear) of the Week. Writers wrote about what they wanted to write about or found interesting rather than being siloed into beats, and they had no firewall between who was allowed to write news or editorials. “It was the purest expression of what I wanted to do in journalism and what I think can be done in journalism,” Craggs said. “It was a model for what journalism should be.”

“Without Numbers, You Can’t Tell the Story: Understanding the Gender Stats Gap in Sports,” by David Berri.

Data is a fundamental part of how sports fans consume their favorite leagues and teams today. But women's sports outlets, from broadcasts to online content, lack the resources to create informed coverage, educate fans, and make the best sports product.

Diana Taurasi attended the University of Connecticut and was drafted by the Phoenix Mercury in 2004. Today, she is the leading scorer in WNBA history. But imagine we asked this question:

Did Diana Taurasi lead the University of Connecticut – the NCAA champion – in scoring in 2003-04?

You would have to think she did. But how would we know?

Before we try to answer this question, let’s imagine we asked a very similar question:

Who led the UConn men’s basketball team – also the NCAA champion that year – in scoring in 2003-04?

A curious person can go to ESPN’s website – the leading sports site – and easily answer the second question. Ben Gordon averaged 18.5 points per game for UConn that year. His teammate, Emeka Okafor, averaged 17.6 points. You can see that Charlie Villanueva, who eventually was a lottery pick in the NBA, averaged just 8.9 points per game. For 2003-04, ESPN shows all the box score stats for every man who played college basketball at UConn. In fact, ESPN reports box score stats for every man who played Division I basketball that season. You can even see that the long-forgotten hoops star David Palmer led Southern Utah University in scoring in 2003-04.

But what about Taurasi? If you look at ESPN, you are out of luck. The site doesn’t report any player statistics for women’s college basketball before the 2009-10 season. Both Bird and Taurasi went to UConn. But ESPN.com can’t tell you what they did as college players.

Remarkably, the same is also true for the NCAA’s website.

“Coverage of Gendered Violence in Sport Improves Through Diversity, Investment and Education,” by Jessica Luther.

Years after gendered violence scandals first rocked the NFL and college sports, U.S. sports media has become better-equipped to report on these crimes. But to accurately and consistently follow these stories, media outlets will need to further education and investment while also diversifying their staffs.

Paula Lavigne has been an investigative journalist at ESPN for the past 14 years. Her work on gendered violence in sports parallels my own timeline, with the first piece she remembers publishing on this topic being from August 2014. Lavigne told me that she also feels the reporting on this topic has gotten better over the years. She said that after the Jameis Winston case at Florida State University, which first surfaced in the news in November 2013 and stretched out for years, “there was a change in how the media responded to these stories,” specifically “how they were taking these reports more seriously.”

Lavigne compared the kind of work happening now to what she saw in newspapers in the 1970s, which she came across recently as she was investigating her latest deep dive, a piece co-authored with Tom Junod, about a Penn State football player who raped multiple women in State College and on Long Island in the late 1970s. “We had the opportunity to go back and look at some of these things'' from that time period, she said, and “reading how the columnist wrote about it made me cringe.”

Lavigne described the newspaper reports as being “so sympathetic to the athletes,” concerned with “how unfortunate it was that he had to deal with [being reported].” Perhaps it’s not particularly surprising to see that framing in a story from over 40 years ago, but Lavigne says that “around the time that I really started to get into this [2014], there was still sort of that tone. ... It almost seemed like it was cast as if an athlete got accused of sexual misconduct or sexual violence or whatever, that it was something that someone did to the athlete, as opposed to the athlete doing something bad to somebody else. And [reporters and columnists] would write about it in the context of how unfortunate it was that he was dealing with this accusation because that meant that he had to miss a game or he had to sit out of practice. ... It was seen as this speed bump in this guy's career.”

“Sports Media Needs More Athlete Apologists,” by Jamal Murphy.

Sports reporters rarely have the same lived experiences as the athletes they cover. This tension is harmful, but it could be better if a more diverse crop of journalists were hired who could truly understand and empathize with athletes.

But today, sports reporters in the United States largely do not represent the athletes they report on. Sports journalists, according to the job market research firm Zippia, are 79.1 percent male, 70.8 percent white, and just 18.3 percent Black or Hispanic. In the three major U.S. sports – football, basketball, and baseball – the majority of athletes are Black and Hispanic at the pro and college levels within both the men’s and women’s games. This disparity in American sports journalism deprives the audience of accurate, balanced storytelling and makes the profession look stale and outdated, like a National Basketball Association team content with playing halfcourt basketball and refusing to use the three-point shot in 2022.

As a result, athletes are often poorly covered because of this lack of diversity at newspapers, TV stations and online outlets. In a recent study from the University of Texas, over 1,000 Black Americans were asked to grade news coverage of Black communities by United States journalists on a scale of 1 to 7. The average of the answers was a paltry 3.3.

Whether it’s bias, ignorance, or outright malice, Black athletes and other athletes of color are often mischaracterized or misperceived by members of the media. When reporters cannot relate to their subjects, their stories come out worse. Athletes who speak differently, dress differently, or express themselves differently in competition are still characterized by many in sports media as negative traits; they are not, of course.

“Women Athletes Are Using Social Media to Make Change and Grow the Game,” by Brian Moritz.

Sports media is still slow to embrace women's sports, even as viewership and fan engagement grows. So women athletes are taking to social media to connect with fans, grow their leagues, and increasingly drive social change beyond the field of play.

There’s no consensus on a single moment when the power of women athletes’ voices in this new media environment became clear. There was the 2016 WNBA-wide protest supporting Black Lives Matter that The New York Times called a “pioneering moment” for the league. Players, who were originally fined by the WNBA for wearing protest T-shirts, held media blackouts and instead posted their messages to Instagram and Periscope. Eventually, the league changed its rules, allowing players to wear shirts advocating for social justice causes.

The U.S. Women’s National Soccer Team used a social-media campaign to push toward wins on pay equity in court and labor negotiations. Players on the USWNT tweeted with the hashtag #EqualPay, creating public support and momentum in their years-long legal fight that ended with a new, equitable contract in 2022. In addition to pay equality, soccer players, most notably Megan Rapinoe, have actively used their platforms to support social justice causes and denounce former president Donald Trump.

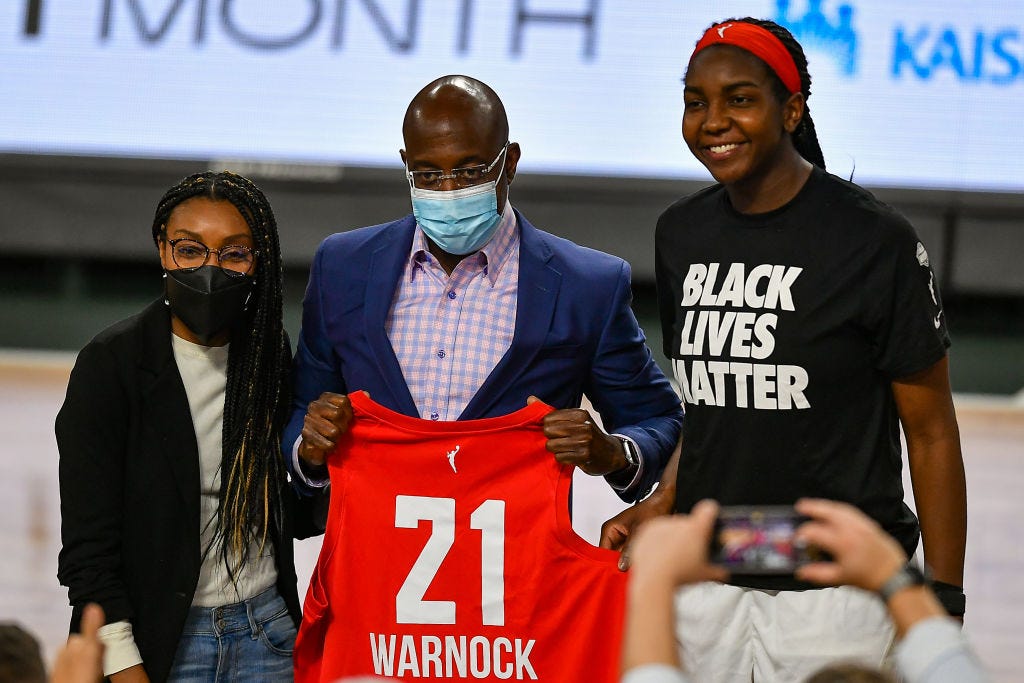

D’Arcangelo points to 2020 protests over George Floyd’s murder and the Dream’s involvement in that year’s elections as a tipping point. Natasha Cloud of the Mystics penned an essay for The Players Tribune on Floyd’s murder, and images of players wearing “Vote Warnock” shirts in the 2020 WNBA Bubble were widespread on social media.

Yanity believes there’s a simple reason that so many women athletes are using their platforms to advocate for political issues – and that those same athletes seem so much better at leveraging social media than their male counterparts.

“So much of women’s sports has just been about the fight to get on the field – literally, just to play,” she said. “Once they’re playing, it’s ‘we don’t want hand-me-down uniforms; we need a trainer’ – all these basic things that men in sports have never had to think about.

“Female athletes don’t know anything else (other) than to fight. You gotta fight just to be on the field, for uniforms, locker rooms, health care, pay. And they see things in their world that they also want to be better, and they’ve been conditioned and bred to fight in this arena of sports, and they just keep doing it.”

“As Digital Media Grows, Traditional Sports Talk Radio Still Prevails,” by Alex Kirshner.

The growth of sports talk radio in the United States gave fans a way to plug into local chatter on the go, and to interact themselves. Though podcasts and other forms of digital media have forced radio shows to adapt, they still play an important and popular role for diehards and casual fans alike.

Sports talk radio is not always pretty – or polished. A caller might ramble on for several minutes. Someone might lose their temper. It’s all live, which means crazy things can happen. Ennis has learned to be comfortable working, as he puts it, “without a net.” But that shagginess, spontaneity, and slight element of potential danger can be charming, and radio is still a more natural place for that sort of dynamic than any kind of pre-produced podcast, even one that fields audience feedback and questions.

“One of the first, best pieces of advice I got in this business almost 15 years ago … is that the best sports talk show is like a ride on a school bus,” says Chris Mueller, a drive-time host at Pittsburgh’s 93.7 “The Fan.” “It’s mostly smooth, but there are enough big bumps in there so that you keep the listener’s attention. The message was pretty clear: ‘Don’t be so polished that it starts to work against you.’”

One other (and likely critical) advantage radio has: It remains the medium for sports teams to air their games for fans who aren’t watching on TV. Those rights-holding relationships, for the stations that have them, give the stations a giant billboard that they can use to advertise the rest of their shows, whether during commercials, those 10-second station identification pauses heard during every broadcast, or the literal signage that so often adorns a home team’s broadcast booth for all to see in a stadium. “It just sort of creates this local culture, at least where people know, ‘If I want to know about what’s going on over there, I’ll start there,’” Ennis says.

This has been Hreal Sports, a newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. If you have any questions or feedback, contact me at my website, www.patrickhruby.net. And if you enjoyed this, please sign up and share with your friends.