Why Marijuana is Winning the Sports Drug War

As America liberalizes its cannabis laws, professional sports leagues are following suit.

Welcome to Hreal Sports, a weekly-ish newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. Sign up and tell your friends!

Editor’s note: The following article was originally published by Arizona State University’s Global Sports Matters. If you’d prefer to read it there in its full glory while supporting a publication that supports yours truly, please give them a click!

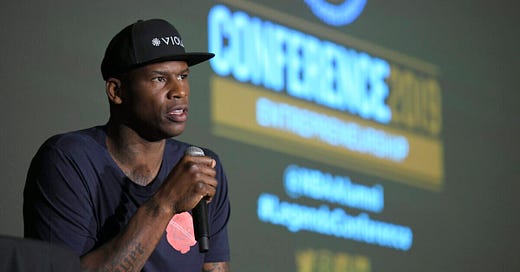

Al Harrington had a plan. It was October 2017, and Harrington, a retired National Basketball Association player turned cannabis entrepreneur and advocate, was interviewing former league commissioner David Stern in his New York office.

Harrington was nervous. Following a 16-year NBA career, he founded a cannabis company named after his grandmother, Viola, who used cannabidiol (CBD)—a component of marijuana that does not produce a high and is used for therapeutic purposes—to treat her glaucoma and diabetes.

Harrington himself used CBD oils and creams for pain relief while playing. Now he wanted Stern, who was commissioner when the NBA added marijuana to its list of banned substances in 1999, to reconsider that policy.

Hoping to lead Stern along, Harrington brought a list of 20 questions, carefully structured to culminate with a Big Ask. “Knowing [Stern] was an attorney for so long, I knew you can’t trick him into anything,” Harrington says. “But I was trying to figure out how to make him make a statement.”

The list wasn’t necessary. Early in the discussion, Stern volunteered that he thought marijuana should be removed from the NBA’s list—and he later added that as medicinal and recreational use of the drug became legal in an increasing number of states, it would be “up to the sports leagues to anticipate where this is going, and maybe lead the way.”

“After that, most people thought he was going to invest in my company!” Harrington says with a laugh. “But he didn’t. He just really believed in what he was saying.”

Three years alter, Stern appears to have been ahead of the curve—both inside and outside professional sports. On Election Day, New Jersey, South Dakota, Montana, and Arizona made recreational marijuana legal, while Mississippi and South Dakota legalized recreational use of the dug.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 15 states and the District of Columbia have now legalized the drug for recreational purposes. A total of 35 states—as well as the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands—have legalized its medical use.

Liberalization of marijuana laws mirrors an increasingly accepting attitude toward the drug by sports leagues. In December 2019, MLB removed cannabis from its list of “drugs of abuse.” The NFL’s recently adopted collective bargaining agreement eliminates suspensions for marijuana use.

Earlier this year, a survey conducted by Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University found that a majority of the American public believes that professional athletes should be allowed to use marijuana: 45 percent of respondents stated that athletes should be allowed to use medical and/or recreational marijuana if such use is legal in their states, and another 24 percent stated that athletes should be allowed to use even if the drug is prohibited in their states.

Taken together, the survey’s results and broader political support for relaxing marijuana prohibition suggest that leagues may be able to further liberalize—or entirely eliminate—existing rules and policies that test and penalize athletes for marijuana use without upsetting fans or harming their bottom lines.

“Societal tolerance is creeping into sports,” says Andrew Brandt, a Villanova University sports law professor and former Green Bay Packers executive. “I was in a [National Football League] front office from 1999 to 2009. Marijuana in general was much more of a taboo than it is now. We looked at players [linked] with cannabis much differently in the draft, free agent, and signing process.

“I’m not in front offices anymore, but if someone yelled, ‘You know, [that player] is a weed smoker,’ I don’t think they’re going to drop in anyone’s evaluation.”

For decades, major sports leagues and organizations have treated cannabis as an illicit drug of abuse, taking a punitive approach to its use by athletes.

At the 1998 Nagano Olympics, Canadian snowboarder Ross Rebagliati won the first gold medal in the history of his sport—and almost lost it after he tested positive for marijuana, a result that landed him in a Japanese jail cell and on the U.S. “no-fly” list, inspired mockery from late-night talk host Jay Leno and “Saturday Night Live,” and helped spur the World Anti-Doping Agency to add the drug to its list of banned substances.

In 2006, NFL running back Ricky Williams was suspended for an entire seasonfor repeatedly failing marijuana tests administered by the league. From 2003 to 2008, 21 American athletes under WADA’s jurisdiction received punishments ranging from public warnings to two-year suspensions for using cannabis-related substances.

More recently, professional athletes including NFL players Josh Gordon and Randy Gregory, NBA players Nerlens Noel and Thabo Sefolosha, and Ultimate Fighting Championship fighters Nick Diaz and Cynthia Calvillo have been suspended for positive marijuana tests.

In 2016, Buffalo Bills lineman Seantrel Henderson smoked marijuana to cope with his Crohn’s disease, a painful condition that ultimately led to him having about 2 1/2 feet of toxic sections of his small and large intestines removed in surgery. The NFL suspended Henderson for 10 games—even though Crohn’s is a qualifying condition under New York’s medical marijuana law.

League and organizations have justified prohibition and punishment as necessary for athlete health and safety. Frequent or high-dose marijuana use has been linked to respiratory, cardiac, and mental health problems, and the drug is considered a Schedule 1 substance—alongside heroin and ecstasy—under federal law. In his interview with Harrington, Stern said that the NBA toughened its marijuana rules partially because “some of our players came to us and said some of these guys are high coming into the game.”

The sports world also has taken a stern stance for public relations purposes, adopting policies that dovetailed with legal restrictions and broader social perceptions. Two years before President Richard Nixon launched the “War on Drugs,” a 1969 Gallup poll found that just 12 percent of Americans believed that using marijuana should be legal—a number that hovered below 25 percent during the “Just Say No” 1980s and stood at 30 percent in 2000, shortly after Rebagliati’s Olympic scandal.

“Cannabis back then was seen as being for losers and lazy stoners,” Rebagliati told The New York Times in 2018. “The big corporate sponsors didn’t want to sponsor me. I became a source of entertainment, a joke. I went from hero to zero overnight.”

Since then, however, much of the stigma surrounding marijuana use has evaporated. From 2005 to 2018, public support for legalizing the drug rose 30 percentage points in Gallup’s poll to 66 percent, where it remained last year.

In 2019, a survey from the Pew Research Center found that 91 percent of American adults believe that marijuana should be legal for either medical and recreational use (59 percent) or medical use alone (32 percent).

Susan Snycerski, a San Jose State University psychology professor who studies the effects of drugs on behavior and currently is conducting a survey of the public’s perception of cannabis use by athletes, says that the same changes can be seen among sports fans.

“Attitudes toward pro athletes using cannabis have gotten more accepting, especially for pain management or for psychological purposes like anxiety,” she says. “And, in general, we see that more avid fans are generally okay with recreational use.”

In the ASU GSI survey, 43 percent of respondents said that they still would be “likely” or “very likely” to purchase their favorite athlete’s jersey or shoe if they found out that athlete used marijuana, with only 16 percent saying that such knowledge would make a purchase “unlikely” or “very unlikely.”

Why the shift? Amy Adamczyk, a sociology professor at the City University of New York, attributes the change primarily to how the media has portrayed marijuana. When support for legalization was low, press reports mostly depicted the drug in the context of crime and abuse.

By contrast, when stories began to frame marijuana use as a medical issue—particularly in the aftermath of a groundbreaking 1996 California state law permitting medical cannabis—support steadily rose. Rather than view the drug as illicit or as a “gateway” to more addictive and dangerous substances like heroin and cocaine, the public began to see marijuana as a physical and psychic pain reliever that was less dangerous than alternatives such as alcohol and prescription opioids.

In 2017, a Marist College poll conducted for Yahoo News found that 72 percent of Americans believed that regular alcohol use posed more of a health risk than regular marijuana use; that nearly one in five marijuana users rely on the drug to help manage pain; and that 67 percent of respondents believed that using a doctor’s prescription for an opioid painkiller posed a greater health risk than medical marijuana.

The same survey also found that if professional athletes used marijuana for pain relief, 69 percent of Americans would approve.

Similarly, a majority of respondents in the ASU GSI survey said that the amount of respect that they have for their favorite athlete would either increase (16 percent) or remain the same (58 percent) if they found out that athlete was using marijuana to treat pain.

“I think the public feels that way because they all smoke, or know someone who does, or know someone who has benefitted from it,” Harrington says. “When you have an intimate relationship with the plant, it shows. You know firsthand that cannabis has medical benefits.”

Harrington speaks from experience. He says that he avoided cannabis altogether until 2012, when he underwent knee surgery while playing for the Denver Nuggets and developed a staph infection.

Harrington was prescribed painkillers, which made him feel foggy. A nurse at a Colorado clinic where he was rehabbing his knee suggested that he try CBD. Harrington found the relief he was looking for—and also realized that alternatives to opioids could be a major business opportunity.

During his final NBA season in 2013-14, Harrington began growing marijuana in a greenhouse. Today, he sells medicinal and recreational cannabis products, and he credits CBD with allowing him to walk without pain despite 13 surgeries.

“In my prime [as a basketball player], you could not talk about cannabis, period,” Harrington says. “Now, I’m probably one of the most popular guys in every room I walk into. Everybody wants to figure out what is going on in the [marijuana] space and how they can participate. And the way players view cannabis is totally different. They are consuming it—and they let people know about it and how they feel about it.”

Harrington isn’t alone in speaking out. In 2015, MMA fighter Ronda Rousey publicly criticized the UFC for suspending Nick Diaz for five years after he tested positive for marijuana, saying she was “against testing for weed at all.” A year later, then-active NFL player Derrick Morgan and eight league retirees partnered with the organization Doctors for Cannabis Regulation to publish an open letter calling on the NFL to consider marijuana a “viable pain management alternative.”

Golfer Robert Garrigus owns a marijuana farm in Washington state, where the drug is legal. He uses medical cannabis to treat knee and back pain. After he was suspended for three months last year for testing positive, he told the Golf Channel that the drug should be dropped from the PGA Tour’s banned substance list because it “doesn’t help you get [the ball] in the hole.”

“I wasn’t trying to degrade the PGA Tour in any way, my fellow professionals in any way. I don’t cheat the game,” Garrigus said. “I understand HGH (Human Growth Hormone), anything you are trying to do to cheat the game you should be suspended for 100 percent. Everything else should be a discussion.

“If you have some sort of pain and CBD or THC may help that, and you feel like it can help you and be prescribed by a doctor, then what are we doing?”

According to ESPN, 101 of the 123 teams in the NFL, NBA, National Hockey League, and Major League Baseball already played in jurisdictions where medical and/or recreational marijuana is legal before November’s elections. The American Journal on Addictions reports that cannabis is the second-most widely used drug among athletes after alcohol.

Faced with those numbers and shifting mores, professional leagues have been liberalizing their marijuana policies—but only to a point. MLB players who engage in “marijuana-related conduct” are subject to a mandatory evaluation and a voluntary treatment program. NFL players remain subject to testing during training camp and are fined for positive results.

The NHL tests for marijuana but neither prohibits nor punishes its use. Instead, players whose tests show “abnormally high levels” of THC are invited to participate in a voluntary substance abuse program.

While NBA commissioner Adam Silver has said that he is open to allowing medical marijuana use, the league has yet to change its cannabis policy.

One roadblock to further reform may be marijuana’s status under federal law. The drug currently is classified as having “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” Possessing, cultivating, and selling cannabis remain criminal offenses, punishable by fines and prison.

In 2018, NBA Players Association executive director Michele Roberts expressed interest in allowing medicinal cannabis but also said that if the league went “down that road, we have to protect our players. … I don’t want my guys being arrested at airports in possession of a cannabinoid by some fed. It’s against the law.”

Sports leagues and organizations may have additional reasons to slow-walk their acceptance: the preferences of older fans. In the ASU GSI survey, 60 percent of respondents over age 60 believed that athletes should not be allowed to use marijuana for any reason. Almost 50 percent of that same cohort said that marijuana use would lead them to having “less respect” for an athlete.

In 2017, a Sports Business Journal study of Nielsen data found that the average age of television viewers for all major American sports was increasing, with the PGA (64 years old), MLB (57) and NFL (50) among the oldest.

“If you think about the amount of money leagues make, they’re going to be conservative,” Snycerski says. “Their business has to come first. I think that you’d have to take away the federal [laws against marijuana] for them to really re-examine it.”

On the other hand, public reaction to state-level marijuana legalization hints that sports entities could continue to loosen their cannabis rules with minimal blowback. Third Way, a center-left think tank, analyzed 10 state elections that took place immediately after the passage of medical cannabis legislation and found that neither voting for nor signing those bills into law hurt incumbent lawmakers at the ballot box.

Harrington doesn’t believe that allowing NBA players to use marijuana would damage the league in the eyes of its fans—or at the ticket window. “I don’t think it will affect them at all,” he says. “Nobody said anything bad about baseball. And we’ll see what happens with the NFL’s changes. I doubt it will be an issue.”

Rather than hurt the business of sports, Harrington says, destigmatizing marijuana use could open up new money-making opportunities for active athletes and organizations alike. In 2016, professional skier Tanner Hall became the first active athlete to be sponsored by a cannabis accessory company; today, soccer star Megan Rapinoe and ultra-marathoner Avery Collins are sponsored by CBD and cannabis companies, while USA Triathlon recently became the first national governing body of an American sport to sign a sponsorship deal with a CBD company.

“In time, I think you’ll see leagues have products that are exclusively created for them,” Harrington says. “That is just the natural evolution of the industry. For pain relief, who is better to speak to that than someone who puts their body through hell every game?”

This has been Hreal Sports, a weekly-ish newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. If you have any questions or feedback, contact me at my website, www.patrickhruby.net. And if you enjoyed this, please sign up and share with your friends.