The NCAA Is Punishing Brittany Collens to Keep Its Amateurism Con Going

The association stripped the former UMass tennis player and her teammates of 49 victories because of a $504 accounting error. Why?

Welcome to Hreal Sports, a newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. Sign up and tell your friends!

When Brittany Collens first saw the news, she figured it was a joke. It was last October, and Collens, a professional tennis player, was driving home following a workout when her coach texted her an article about the National Collegiate Athletic Association punishing the University of Massachusetts, Amherst women’s tennis program for violating its amateurism rules.

Didn’t you play at UMass? her coach texted.

Collens did. As a senior in 2017, she helped the school win its first Atlantic 10 title in 15 years, capping a memorable season for Collens and her tight-knit teammates with what she calls “an absolutely fairy-tale ending.”

But now—three years later and completely out of the blue—the clock was striking midnight. After pulling off the road, Collens read the article. The NCAA was vacating 49 UMass women’s tennis victories from 2014-15 to 2016-17, including the team’s conference championship, because two players had received money from the school exceeding the full cost of attendance—thereby flouting the sacred and fundamental principle that college athletes shall not get more than whatever the NCAA says they are allowed to get, currently the value of their athletic scholarships plus cost of living stipends.

Curiosity curdling into disbelief, Collens realized that she and her former roommate, Anna Woosley, were the two players in question. Their terrible, no-good amateurism crime? When the pair moved out of dorms and into off-campus housing during their junior year, the school mistakenly continued to include a $252 telecommunications subsidy in their scholarship checks.

“It’s a stipend for athletes in on-campus housing, so they can have a phone jack for a landline,” Collens says. “I didn’t have a landline when I lived on campus. So I never even noticed it. I had to call my former coach and the UMass [athletic director] so they could explain what was happening, and why I was in trouble.

“It just doesn’t make sense. The rules don’t make sense.”

Collens is right: NCAA rules that turn college athletes into second-class economic citizens forbidden from earning whatever somebody wants to pay them do not, in fact, make a whit of sense. There is no morally justifiable reason to prevent Zion Williamson from signing a shoe deal while playing basketball at Duke University, prohibit University of Minnesota wrestler Joel Bauman from selling his rap songs on iTunes, sanction University of Central Florida kicker Donald De La Haye for making money from his YouTube channel, or crack down on California Polytechnic State University because some of its athletes received too much textbook funding. Particularly not when the NCAA purportedly exists to support the “well-being and lifelong success of college athletes,” and cash in one’s pocket continues to be (surprise!) a key variable in furthering both.

On the other hand, amateurism’s sheer nonsensicalness is exactly why the NCAA and its member schools have no choice but to pretend otherwise—and why an unintentional accounting error worth about as much as a nice tennis racket has resulted in the bulk of Collens’ collegiate tennis career being declared null and void. Like the Wizard of Oz, the people who run college sports have a grand illusion to maintain, the myth that their rules are somehow sacrosanct. And that means enforcing them as such.

Otherwise, the whole con falls apart.

The details of how the NCAA came for Collens are both absurd and illustrative, a Joseph Heller B-plot come to life. The story begins in 2017, when just-hired UMass men’s basketball coach Matt McCall was asked by one of his players about getting free tickets to an on-campus concert—something other players previously had received.

Worried that the free tickets could constitute a NCAA rules violation, McCall brought the issue to UMass athletic director Ryan Bamford. Bamford’s department looked into the matter, ultimately determining that the tickets did not break amateurism rules because they were free to all students. (Phew! Crisis averted!) During that process, the department also realized that a handful of men’s basketball and tennis players who had moved from on-campus to off-campus housing had received more money in their scholarship housing allowances than they were supposed to—not because UMass was surreptitiously trying to slip its athletes some extra cash (which, frankly, would have been cool and good), but rather because the school had made an accounting error. UMass hired an outside law firm that specializes in NCAA-related cases to conduct an internal audit, which found that 12 athletes received roughly $9,100 in excess housing money.

Of that total, a combined $504 went to Collens and Woosley. “We would just get, like, lump sum direct deposits into our bank accounts [for our housing expenses],” Collens says. ““I didn’t even know I was getting any extra money. And my bank account never went below $252, so I didn’t even spend it!”

In a totally sane college sports world, none of this would have mattered, because none of it would have been against any rules. McCall and Bamford wouldn’t have wasted their time worrying about free concert tickets. UMass wouldn’t have wasted time and money—reportedly $100,000—hiring an outside law firm to investigate an internal clerical mixup. Even in a semi-sane college sports world, said investigation would have been the end of things: maybe UMass would have asked Collens and the other athletes to pay back their puny housing allowance overages, or maybe the school simply would have eaten a financial loss so insignificant that nobody working there even noticed it had happened until accidentally stumbling across it.

Alas, the college sports world is governed by the NCAA. So things played out as stupidly as possible. UMass self-reported the overpayments to the association, which otherwise would not have known about them, and agreed to pay a $5,000 fine. In return, the NCAA took the school’s money—and also vacated nearly 100 combined men’s basketball and women’s tennis victories from the 2014-15, 2015-16, and 2016-17 seasons, explaining that “the excessive financial aid rendered the student-athletes ineligible. NCAA rules require member schools to withhold ineligible student-athletes from competition until their eligibility is restored, regardless of the school’s knowledge.”

In other words: Here’s your speeding ticket. Next time, don’t drive 57 miles per hour in a 55 mph zone, and definitely don’t admit as much to the cops. Rules are rules.

The NCAA’s decision left Collens perplexed. For the sake of a bookkeeping screw-up she didn’t make, an amateurism violation she didn’t understand, and a purportedly ill-gotten financial windfall so penny-ante that UMass couldn’t find it without hired help, an organization founded to protect the health and safety of athletes was instead dropping her college career into a memory hole.

Collens thought about how hard she and her teammates had worked to win matches. “I felt sad for our group,” she says. “I talked to them. They’re heartbroken. I know what those victories meant, especially to my teammates who are international—who packed up and moved away from their families, who had their families joining in to watch them play on live video streams at, like, two in the morning their time.” She thought about Woosley clinching the A-10 championship on the final point of the final match to cap an improbable UMass comeback against Virginia Commonwealth University, and how the team literally went to Disney World to celebrate. She thought about what the NCAA essentially branding them as cheaters would mean for their futures.

“I was worried about our reputations,” Collens says. “The NCAA is saying we did something wrong. I know some of my teammates have used that championship in their job interviews. I’m still a professional tennis player. What if people really think that about me? Will I ever be able to get another wild card [entry] into a tournament?”

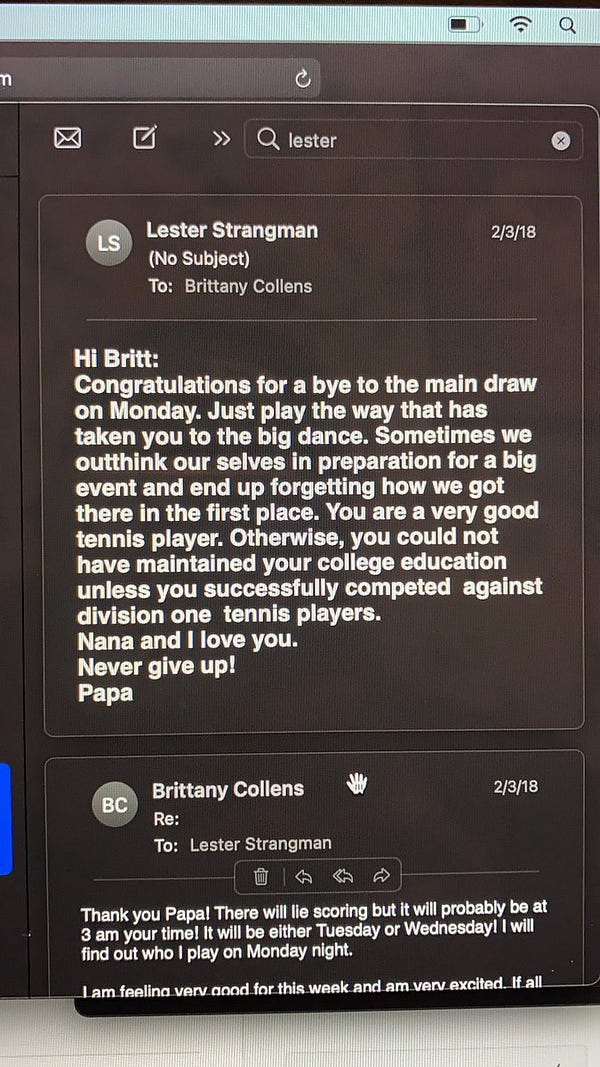

Collens thought about her grandfather, Lester, a nonagenarian who would drive two hours to watch her UMass home matches and regularly sent his granddaughter heartfelt messages of inspiration and support before his death in 2019. Her confusion was replaced by anger. “What would my papa feel if he knew that this is what the NCAA was doing?” she says. “That’s why it’s emotional for me. It’s a slap in the face.”

Collens isn’t the first college athlete to feel the sting of the NCAA’s absolutist justice. From football to basketball to soccer, athletes have been punished for high amateurism crimes and misdemeanors including using a Xeroxed faculty parking pass during winter break, having one’s stepmother receive a discounted rate at a campus hotel, and eating more pasta than permitted at a graduation banquet.

All of this raises a question. Why? Why go full broken windows, vigorously policing picayune stuff? Why send a SWAT team to put down a housefly? Why not show the slightest bit of commonsense enforcement discretion by leaving athletes such as Collens alone?

The answer lies in how the NCAA defends its rules against legal challenges in federal court—by pretending that amateurism is a matter of principle, not price.

To be fair, this defense is a pretty good magic trick. By which I mean a scam. Even Oscar Diggs would be impressed. To understand the NCAA’s devotion to it—and its parallel indifference to athletes ending up as collateral damage—it helps to understand the nature of those legal challenges. So let me explain with a quick analogy.

Imagine you’re a restaurant owner. A brilliant young chef has just moved into your town. You want to hire her. So do the owners of five other restaurants. One offers the chef a high salary. Another offers better health benefits. You offer both, plus a generous signing bonus.

You land the chef. But it costs you. And over time, all of this darn bidding drives up labor costs for you and your competitors alike. So you get together and make a pact: from now on, nobody pays more than $50,000 a year for a chef. No exceptions.

The pact pays off for everyone. Handsomely! The chefs have no choice but to accept your offers—in fact, it’s a privilege for them to work in your restaurants. And with all the money you’re saving on salaries, you can afford to pay yourself more. Or put a lazy river in your parking lot.

Pretty sweet deal, right? For sure. It’s also completely freaking illegal. Federal antitrust law, which exists to protect and promote economic competition, prohibits this sort of collusion. Usually. However, if an agreement among marketplace rivals is necessary for a product to exist in the first place, like the USB interface standard in electronics, then that agreement can be considered “procompetitive” and allowed to exist.

Back to college sports. Think of the NCAA and its members schools as restaurants, and athletes as chefs. Over the last decade, athletes including former University of California, Los Angeles basketball player Ed O’Bannon repeatedly have sued the association in federal court, arguing that amateurism violates antitrust law. In response, the NCAA has claimed its rules prohibiting athlete compensation are procompetitive for a number of reasons, including preserving competitive balance among schools, promoting athletes’ educations, and allowing athletic departments to field teams that don’t make money.

One by one, these reasons have been discredited in court. And rightfully so, because they’re—to use a legal term of art—total bullshit. Amateurism has not put the men’s basketball programs at the University of Kentucky and Ball State University on a level playing field. It does not make college athletes better students, despite NCAA president Mark Emmert’s contention that paid players probably wouldn’t eat in school cafeterias, which in turn could hurt their studies, which is an actual argument Emmert made in a federal trial, and an actual sentence I just typed. Nor is amateurism necessary for men’s track and other non-revenue sports to exist; if it was, athletic departments crying poverty during the coronavirus pandemic wouldn’t be slashing those programs while simultaneously paying football coaches millions of dollars to not work.

Today, the NCAA is down to a single procompetitive defense for amateurism: if college athletes were paid, the association claims, then there would be no difference between professional sports and college sports—and importantly, fans would no longer tune in to or buy tickets for the latter. Outside of campus athletic directors saying so in depositions, there’s no concrete evidence that this claim is true. Nevertheless, federal judges have bought it. Case in point? After Judge Claudia Wilken ruled in O’Bannon’s case that schools could pay athletes up to $5,000 a year through trust funds those athletes could access following the end of their college careers, an appeals court struck that provision down, reasoning that:

… the difference between offering student-athletes education-related compensation and offering them cash sums untethered to educational expenses is not minor; it is a quantum leap. Once that line is crossed, we see no basis for returning to a rule of amateurism and no defined stopping point. (Bold added).

The logic here is simple: if amateurism exists to uphold a particular price point for athlete compensation instead of a existing as a product-defining principle—if it’s a highfalutin excuse for a salary cap instead of the mystical and inviolable line between college sports and the void—then there’s no reason for the federal judiciary to keep protecting it. Pay athletes $5,000 in deferred compensation, and you might as well pay them $500,000 in straight cash, homey.

In reality, of course, amateurism has always been a price-fixing scam. Once upon a time, athletic scholarships counted as pay. Then they didn't. Laundry money given to athletes didn't count as pay. Then it did. The NCAA was deeply, existentially opposed to both cost-of-living stipends and complimentary bagel toppings—that is, until bad press and expensive lawsuits convinced Emmert and company that, actually, cream cheese should be spread liberally, that gas and pizza money won't break the bank of an industry that can afford to pay football strength coaches $525,000 per year, and that we have always been at war with East Asia. In the here and now, the NCAA allows plenty of quantum leaps into compensation that have nothing to do with educational expenses, with athletes getting PlayStation 5s for playing in the Fiesta Bowl, $740,000 from the government of Singapore for winning Olympic gold medals, and actual, honest-to-goodness salaries for playing sports at service academies.

But pay no attention to those glaring inconsistencies. Akin to Oscar Diggs barking about the great and powerful Oz while furiously working the assorted levers and doodads behind his chintzy green curtain, the NCAA puts real effort into make-believing that amateurism is more than a grubby price-fix—effort that includes dropping the hammer on absurd rules violations, like unknowingly receiving phone jack money. Rules are rules, after all. Allow college athletes to cross the amateurism line by receiving even $252, and people might start to wonder why there’s a line in the first place, or whose interests that line really serves.

During her time at UMass, Collens didn’t give those interests much thought. She was too busy practicing and playing tennis, studying sports journalism, and trying to get through days that started as early as 5 AM and often ended after midnight. “You’re told to be grateful,” she says. “I was super grateful to have a scholarship. And if you don’t perform, you could lose that scholarship. So that’s kind of where I was.”

Besides, NCAA amateurism rules were confusing, simultaneously abstract and arcane. At the start of each school year, Collens and other athletes would sit through compliance meetings—complete with paperwork and PowerPoint presentations—informing them exactly what they were allowed to receive and do. “There’s so many rules,” Collens says. “It’s boring to sit there for a couple of hours. You’re tired. You’re falling asleep. And for me, with tennis, are they really worried about us, like, taking boosters’ money? We didn’t really have boosters.

“Honestly, I probably didn’t know all the rules when I was playing. I would just hope that I was doing the right thing.”

Today, Collens wants the NCAA to do the right thing. Hours after she learned about the association’s punishment, she started an online petition to have UMass’ tennis victories reinstated. The petition has since attracted more than 7,500 signatures; meanwhile, Collens has shared her story with the Boston Globe, ESPN, the Burn It All Down podcast, and local television.

UMass is appealing the NCAA’s penalties, and both school athletic director Bamford and A10 commissioner Bernadette McGlade have expressed public disapproval of the association’s decision. (So have four Massachusetts district attorneys who graduated from the school). A favorable ruling, Collens says, would make her happy. But not satisfied. Not anymore. Ironically, the NCAA’s heavy-handed amateurism enforcement has a way of inspiring people to peek behind the curtain.

Over the last two months, Collens has spoken with Taylor Branch, the Pulitzer Prize-winning civil rights historian whose definitive 2011 takedown of amateurism, “The Shame of College Sports,” still stings; with Sonny Vaccaro, the former Sneaker Don who has become an outspoken advocate for college athletes’ rights and was a driving force behind O’Bannon’s seminal lawsuit; with Andy Schwarz, an influential economist who has consulted on NCAA antitrust suits and written extensively about amateurism’s failings; with Tim Nevius, a lawyer and former NCAA investigator who now works on behalf of college athletes; and with a legislative aide to Sen. Cory Booker, who last December introduced a bill in Congress that would give athletes a share of the profits generated by college sports and create government oversight of health and safety standards.

Those conversations have left Collens questioning much more than just her own team’s vacated victories. Why did UMass have to spend $100,000 defending itself in the NCAA’s kangaroo court when that same money could have gone directly to supporting athletes? Why does the association zealously police amateurism, but not the emotional, physical, and sexual abuse of athletes? Why do the people in charge of college sports get to tell athletes what they can and can’t earn? “It’s super mind-boggling how much I didn’t know before this,” Collens says.

Last year, a former financial adviser named Marty Blazer was facing up to 67 years in prison after pleading guilty to defrauding five clients—most of them professional football players—out of $2.35 million. He instead was sentenced to one year of probation, perhaps in part because the NCAA wrote a letter to the court asking for sentencing leniency. Why intervene on behalf of a conman and a thief? Blazer also was helping the association identify amateurism rule breakers, basketball players and recruits who allegedly were receiving under-the-table payments. The people running college sports were willing to go to bat for a man who was pickpocketing athletes, so long as he could help them prop up a system that does the same. It sounds like a joke. A cruel one. “We’re told that the NCAA is protecting us,” Collens says. “But I’ve realized that their rules are actually just meant to keep us in line. They are not for our benefit at all. I probably wouldn’t have said that a few months ago. But I’m starting to understand how wrong it is.”

This has been Hreal Sports, a newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. If you have any questions or feedback, contact me at my website, www.patrickhruby.net. And if you enjoyed this, please sign up and share with your friends.