The Mystery of 9/11 First Responders and Dementia

Many first responders are experiencing alarming cognitive decline. Is their time at Ground Zero to blame?

Welcome to Hreal Sports, a weekly-ish newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. Sign up and tell your friends!

Editor’s note: The following article was originally published by The Washington Post Magazine in September 2021. It’s also very much not about sports. If you’d prefer to read it there in its full glory while supporting a publication that supports yours truly, please give them a click!

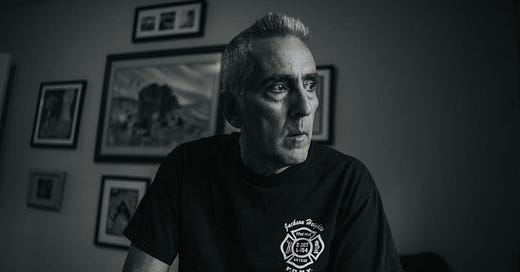

More than a decade after the twin towers fell, Ron Kirchner began forgetting things. Buckling his belt. Closing his car door. Once, while visiting a preschool class on the 13th anniversary of 9/11, he even neglected to wear his customary necktie and New York City Fire Department hat. “He was in a panic,” says his wife, Dawn. “He used to like to bring the kids something, like coloring books. And he couldn’t find anything.”

This was unlike Ron, who had always been devoted and dutiful. He frequently wrote Dawn love notes, hiding them around their house. He made time after work to play with his two children, Luke and Ava. He mopped the floors before going to bed, whistling while he pushed the handle. “He did it joyfully,” Dawn says. “Ronnie was a giver.” Ron brought the same enthusiasm to his job as a firefighter in Queens, where he obsessively cleaned his truck, stayed up all night waiting for calls, and — according to unit lore — once smashed an Xbox with an ax because he thought that some of his younger colleagues were spending too much time playing video games. “Dad thought they should be reading up on fire stuff, training and procedures,” Luke says with a laugh.

Ron was one of the tens of thousands of police, firefighters, construction workers and others who worked amid the ruins of the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan following 9/11. Like many of those responders, he later paid a price. Diagnosed with asthma and a lung disease both linked to Ground Zero exposure, Ron retired on disability in 2009 and moved to Arizona.

At first, life in the desert was good. Ron landed a comfortable job working private security for a wealthy client. He and Dawn visited the Grand Canyon. They saw the red rocks of Sedona. Ron would wheeze while hiking, and sometimes at night, but a nebulizer made his breathing less strained.

By 2014, however, Ron’s troubles with thinking and memory were becoming unmanageable. Back in New York, he had deftly maneuvered a fire engine along the city’s crowded streets; now, he struggled to parallel park the family’s SUV inside two spaces. He would put toothpaste on his toothbrush and not know what to do with it. He was let go from his security job — in part, Dawn says, because he struggled to use a smartphone.

One day in early 2015, Dawn received a call from her husband’s naturopathic doctor, who had given Ron the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, a brief test that screens patients for cognitive disorders. Ron had scored poorly, unable to draw a simple clock face with the correct time. Dawn took him to a neurologist, who diagnosed him with dementia. Ron was 52. The neurologist, Dawn says, told her that a magnetic resonance imaging scan of his brain was comparable to that of an 85-year-old.

Today, Ron suffers from seizures. He can no longer speak coherently, cut his own food or bathe himself. He requires round-the-clock care and supervision from his wife and children, lest he wander into the streets around his family’s home in Oceanside, N.Y., where they moved in 2017. “He doesn’t really know who I am,” Dawn says, “or who he is, or what his favorite thing in the world — the fire department — is.” She doesn’t think Ron knew he was being photographed for this article, and believes it would have been impossible to explain it to him. But Dawn feels that it’s important to share his story as a way of helping others — and that her husband, if he could still understand, would feel the same.

Ron’s condition is almost unheard of for a 59-year-old man, and it points to an emerging medical mystery: Twenty years after 9/11, Ground Zero first responders are suffering from abnormally high rates of cognitive impairment, with some individuals in their 50s experiencing deficiencies that typically manifest when people are in their 70s — if at all.

“That is the most extraordinary thing with these cognitive issues, and what blows me away,” says Benjamin Luft, director of Stony Brook University’s World Trade Center Health and Wellness Program, which cares for and studies responders. “You don’t expect this to occur in your 50s, because it doesn’t occur. And a lot of these people are in their early 50s.” Although most cases are not as severe as Ron’s, the number of responders showing memory loss and other signs of impairment has been rising over time. Scientists and doctors are now asking: Is 9/11 to blame?

On the night of the attacks, Ron Kirchner arrived in Lower Manhattan with a group of firefighters. Bewildered by the sheer scale of the devastation, they froze — until someone in the group spoke up. What are we waiting for? Let’s go. “From that point on,” Luke Kirchner says, “they were working like crazy.”

When the planes hit the towers, it triggered an almost inconceivable catastrophe. Collapsing buildings pulverized hundreds of thousands of tons of cement, steel, glass and other materials, along with thousands of computers, miles of electrical cables, and hundreds of thousands of gallons of heating and transformer fluids. The destruction created a blizzard of pinkish-gray dust that seemed to coat everything; beneath the piles of rubble, jet fuel ignited fires that burned and smoked across a 16-acre area until Dec. 19.

Seven days after the attacks, Environmental Protection Agency administrator Christine Todd Whitman reassured the public that the air around Ground Zero was safe to breathe. It was not. (In 2016, Whitman apologized for her remarks.) The dust contained glass fibers and other particles small enough to lodge deep in the lungs, as well as many substances and chemicals that are known toxins — including asbestos lead, and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), a category of odorless compounds whose manufacture in the United States was banned in the late 1970s after they were linked to cancer. In 2003, an atmospheric scientist described the area’s smoking wreckage as a pollutant-spewing “chemical factory.” Four years later, an EPA analysis of Ground Zero air quality in the days following 9/11 found that ambient levels of dioxins — another group of chemical compounds known to cause cancer and other maladies — were the highest measurements “ever recorded anywhere in the world.”

Reneé Totaro, then a New York City police officer, arrived at Ground Zero on the same night as Ron Kirchner. She worked there for the next three months. Now retired, she says she will never forget the smell. “It was so strong, almost like acid,” says Totaro, 52. “You could taste it in your mouth. Our eyes were burning. Our throats were burning. Our ears were burning.”

The physical stress was compounded by emotional trauma. Responders saw things no one should. Richard Roeill, a retired Nassau County firefighter and rescue swimmer who spent months sifting through the ruins, remembers searching a space under the remnants of Windows on the World, the famous restaurant that had occupied the top floor of the North Tower. Crouching below a beam, he saw a desk, a computer, a datebook — and then, a piece of fabric. “It was just slimy,” says Roeill, 59. “Almost like a greased rag. It looked like a female garment. Things like that still bother me.”

After two weeks on “the pile” — the term many responders used to describe the 1.8 million tons of debris they searched and ultimately removed — Roeill began coughing, suffering nosebleeds and throwing up. Totaro experienced migraines, a sinus infection, blurred vision and a perpetually upset stomach. “I was just chugging Pepto Bismol,” she says. “I didn’t even need to use the cap” to measure. Both continued to work — as did Ron Kirchner, who spent nearly 600 hours at Ground Zero, signing up for a series of 30-day stints until March 2002.

“We had family members and friends of [missing people] giving us pictures, saying, ‘Please, if you see my husband, my brother,’ ” Roeill says. “I went down there thinking I was going to save the world. That I was going to bring someone home. And I know that was going through the head of the guy next to me, and the guy next to him.”

Over the following weeks and months, many responders developed what doctors later dubbed “World Trade Center cough,” a syndrome that often includes shortness of breath, nasal congestion and acid reflux. Others suffered from nightmares and anxiety attacks. For some, the problems were temporary. But for others, they persisted — or got worse. In the years since the attacks, a wide range of chronic health conditionslinked to 9/11 have emerged: asthma and sinusitis, sleep apnea and depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and a laundry list of cancers. Studies have found that New York City firefighters who worked at Ground Zero are at increased risk for heart disease, and that people exposed to the dust cloud have a higher risk of developing autoimmune disease.

Before 9/11, Totaro had an undiagnosed autoimmune disorder. It flared up at Ground Zero and nearly caused her to lose sight in her right eye. She retired from the police in 2004 when her compromised vision made it hard for her to hit targets at a shooting range.

Roeill once played bagpipes in a firefighter band. At work, he used to be able to hold his breath for up to three minutes underwater. He now sleeps with the help of an oxygen machine and spends four days a week being treated for PTSD, pulmonary disease and toxic metals in his blood. “When I talk,” he says, “I feel chest pains.”

Luft, the director of Stony Brook’s WTC Health and Wellness Program, is a renowned infectious-disease specialist who developed some of the first treatments for Lyme disease and AIDS-related infections. On 9/11, he spent the day preparing the Department of Medicine at Stony Brook University Hospital for an expected influx of wounded people. No one arrived. Survivors were too scarce. Days later, he visited Ground Zero; upon returning to his office on Long Island, he began establishing a clinic to care for responders.

His efforts and others like it have evolved into the World Trade Center Health Program, which is administered by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and provides medical monitoring and treatment to more than 100,000 responders and survivors through a nationwide provider network and at seven clinical centers in New York and New Jersey. Enrollment in the program has increased over time, and doctors continue to see new and unusual ailments. In 2018, for example, researchers found that firefighters who worked at Ground Zero are at elevated risk of developing a rare variant of a blood cancer precursor disease that was also more common among Vietnam War veterans exposed to the toxic herbicide Agent Orange. “The asthma that [9/11 responders] have is not typical asthma,” Luft says. “The sinusitis is not typical sinusitis. The GERD [gastroesophageal reflux disease] is not typical GERD, where you just take a Tums” to treat it.

Like Totaro, Luft still remembers the smell at Ground Zero — and an unsettling realization that the fallout would be ongoing. “What I knew right away was that this was something that had not been seen before,” he says. “There have been other mass disasters, like Fukushima and Chernobyl. But this was a unique combination of prolonged and complex physical and psychological exposures. So it would be totally unpredictable as to what the [long-term health] problems would be.”

In 2014, Sean Clouston began to see a disturbing trend. An epidemiologist and professor of public health at Stony Brook University, he had suggested giving the Montreal Cognitive Assessment to some of the nearly 8,000 responders, mostly living on Long Island, who were being followed by Luft’s clinical center. On 9/11, many had been in their late 30s. “They were now in their 50s, so I thought we should get a baseline to see where they were and help us follow up later,” Clouston says. “We didn’t anticipate that many of them would have problems.”

But they did. Of the 818 responders Clouston and his colleagues first tested, 104 had scores indicative of cognitive impairment, a condition that can range from mild to severe and that occurs when people have trouble remembering, learning new things, concentrating or making decisions that affect their everyday lives. Ten others scored low enough to have possible dementia. Clouston was stunned. As a group, the responders were relatively young. Many had to pass mentally demanding tests to become police officers and firefighters in the first place. They were some of the last individuals you would expect to be impaired, let alone at roughly three times the rate of people in their 70s. “We should have seen — maybe — one person” with dementia, he says. “And we had way too many people showing impairment. It looked like what I’m used to seeing when we study 75-year-olds. It was staggering.”

When Clouston first shared his findings in a meeting, Luft had one thought. No way. “I couldn’t believe it,” he says. The researchers double-checked their work, making sure they were using the cognitive test properly. Still worried that something was amiss, they gave more than 1,000 responders a different test that measures reaction time, processing speed and memory. In each area, responders performed below the norm for their age group — and almost 15 percent had scores consistent with cognitive impairment.

Since then, other studies from Stony Brook researchers have found that within a group of 1,800 responders who were initially cognitively healthy, 14 percent developed impairment over a 2½-year period, and that responders with PTSD and impaired cognition have both blood and brain protein abnormalities similar to those seen in patients with Alzheimer’s and related diseases. “We are slowly getting pieces of the puzzle,” says Stephanie Santiago-Michels, a research coordinator for Stony Brook’s WTC Health and Wellness Program. “We know that their brains are changing.”

At the program’s clinic in Commack, N.Y., responders have told research program coordinator Alison Pellecchia about getting lost while driving in their own neighborhoods and struggling to figure out how much money to give cashiers. Some have trouble recalling anything that they don’t write down — including coming in for lab tests and brain scans. “They always feel horrible about that,” Pellecchia says. “They’ll tell me, ‘I’m doing a study about memory, and I can’t remember my appointment!’ ”

The evidence that 9/11 was responsible may not be definitive, but it is difficult to ignore. The air at Ground Zero contained chemicals and microscopic particles that are toxic to brain cells and have been linked to higher risk of Alzheimer’s and other dementias. Clouston’s group has found elevated levels of a protein linked to neuroinflammation in the brains of responders, with higher amounts corresponding with having spent more time on the pile. In a 2017 experiment, Michelle N. Hernandez, then a doctoral student at New York University, injected Ground Zero dust into the nasal passages of mice. The mice subsequently suffered neuroinflammation, and metals associated with the dust were found to persist in their brains.

“Pollutants aren’t good for your brain in animal studies,” says Stony Brook research professor Erica Diminich. “If you put a rat in a little chamber and blow a bunch of fumes and exhaust into it over a period of weeks, it’s not looking too good for the rat. So it’s not a stretch to say that [Ground Zero air] could have some detrimental long-term effects on responders.”

And the explanation may not only be physical. When Clouston was a child, he was careful not to wake his grandfather, a World War II veteran, from naps. “If you surprised him, he would [try to] hit you, because he thought you were a German” soldier, Clouston says. “My grandfather had PTSD to the last day of his life.” Many responders have PTSD, in which people suffer from a variety of physical and emotional disorders — including flashbacks and difficulty sleeping — after experiencing dangerous or terrifying events. Among the responders Clouston has studied, PTSD correlates with lower scores on cognitive tests. And a study of New York City firefighters and paramedics conducted by the New York City Fire Department and researchers from the City University of New York and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine found that those who had more intense exposure to Ground Zero were more likely to report cognitive concerns and elevated PTSD levels than those with less intense exposure.

Clouston says that toxic air and PTSD could both be culprits — perhaps even joint accomplices, acting as a “one-two punch” to responders’ brains. “We’re trying to understand that,” he says. “Some of it is impossible to tease out.” Many other important questions remain unanswered. Why are some responders fine, and others anything but? Are they suffering from a variation of a known neurological ailment, or something unique? Did Ground Zero exposure simply fast-forward the arrival of cognitive problems that naturally occur with advancing age? What role do genetics play? Will impaired individuals decline into dementia, like Ron Kirchner?

Seven years ago, Luft’s initial skepticism was shared by many in the larger medical community. “People said this was impossible, that [the responders] must not have anything because they are just too young,” Clouston says. “And we still hear that.” Those doubts are changing, however. In October 2019, the WTC Health Program gathered expertsfrom across the country for a two-day meeting in Alexandria, Va., to discuss responders’ cognitive problems. Caleb Finch, a University of Southern California professor who studies how environmental factors contribute to Alzheimer’s and accelerated brain aging, was in attendance. “There’s a large amount of uncertainty, and the data is just in the beginning of being collected,” he says. “But everyone there I talked with said this is something we ought to look at very seriously. It’s clear that this is a lingering brain insult, 20 years later.”

In their published studies, Clouston and his colleagues are careful to use the term “mild cognitive impairment”instead of “dementia.” So much remains unknown, Clouston says, and “we don’t want to scare anyone.” But recently, he says, other scientists looking at the same data have started to give unexpected feedback. “They say our language is too soft,” Clouston says.

Dawn Kirchner, 57, sits in her dining room, trying to explain life with Ron. Lacking the right words, she pulls up her sweater sleeves. She is not physically imposing: At 5 feet tall and 95 pounds, she’s a foot shorter and 120 pounds lighter than her husband. Her biceps, however, are well developed. “I never had these before,” she says.

The work starts early. It never really ends. Ron wakes up between 5 and 6 a.m. He likes to walk around the house. Dawn makes breakfast, cuts his food into small bites — so Ron won’t choke — and feeds him as he comes and goes from the kitchen, one forkful at a time. She then shaves his face, brushes his teeth and gives him anti-seizure medication.

Some mornings, Ron will nap. Some mornings, he won’t. Nothing is predictable, and everything is fraught. Ron swallows his toothpaste. He struggles to step into the shower. He resists when Dawn tries to change his pants, or take off his shoes, or get him in and out of their car. “At one point, he was infatuated with my slippers and would put them in his mouth,” she says. “It’s very erratic. You have to be able to deal with that.”

Before Ron slid into dementia, he and Dawn would take daily, hour-long walks. Today, anything over 15 minutes is a challenge. In the afternoons, Dawn drives Ron to a coffee shop, then to a nearby lake to look at geese. “He used to love birds,” she says.

On good days, Dawn and Ron will follow that with another short walk. On bad days, they’ll stay in the car. If Ron wets or soils himself, Dawn will go home and clean him up; otherwise, she’ll drive around Long Island, expressing gratitude. You were the best husband. You worked so hard to take care of us. “It maybe keeps my sanity,” she says.

They met in the summer of 1989. Fresh from graduate school, Dawn was living with her parents. Ron was helping to build a deck for the house next door. One day, he approached her. Hey, are you married or anything? “I had a boyfriend at the time,” Dawn says with a laugh. “But Ronnie was cute.”

Dawn learned that Ron had grown up in Spanish Harlem, and that his father died when he was a toddler. As a child, he idolized firefighters; after he became one in his late 20s, he began wearing a custom fire department belt buckle. “Nobody does that,” son Luke says.

Ron was hard-working, full of seemingly inexhaustible energy. He lived to take care of others. In addition to his day job, he had his own construction company and sometimes drove a limo. He was the person Dawn’s sisters would call when they had plumbing problems, a Mr. Fix-It who spent his free time renovating his family’s house and building decks for his neighbors. “Ronnie would clean the pool and then call me from work just to ask, ‘Is your father in the pool? Your friends? Are you enjoying it?’ ” Dawn says. “That brought him joy.” Later, when he was losing his ability to speak, he would still hold doors open for strangers while out shopping.

Ron didn’t talk much about his time on the pile. After 9/11, Luke says, his father attended funerals and “wasn’t home a lot.” Dawn believes that Ground Zero triggered his dementia, just as it almost certainly was responsible for the breathing problems he developed in the late 2000s. “He had so much exposure,” she says. Back then, she didn’t think about what was in the air in Lower Manhattan, or how it might be harmful — and even now, she’s not sure her husband would have cared. “If he knew what we know now, do I think he would have done anything different?” she says. “Absolutely not. And not just him. Most of” the responders.

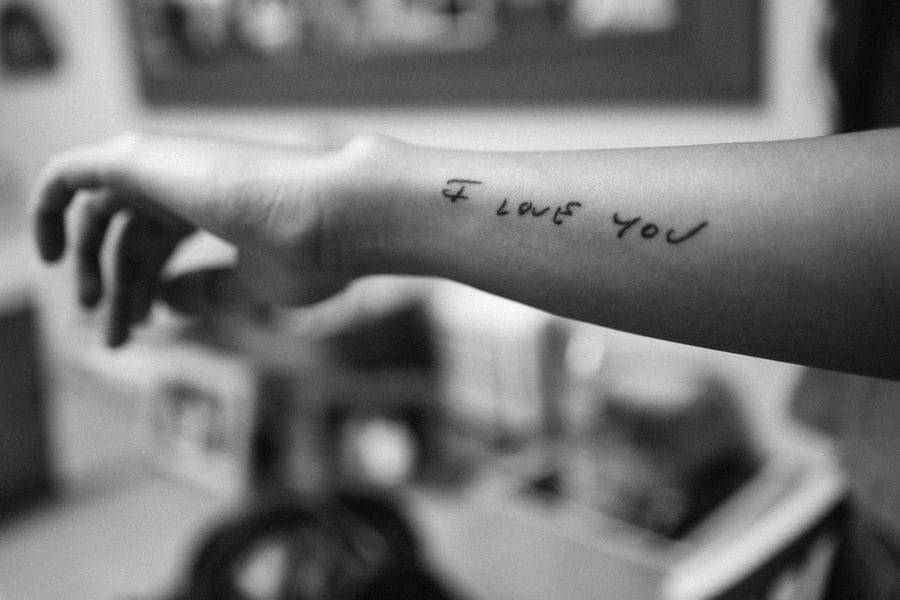

Dawn and her children now live in limbo. Ron is still here. But the man they knew is mostly gone. The family holds on to what they can, remembering what Ron can’t. Luke, 25, treasures his father’s old tools. He wants to become a firefighter. Ava, 20, has a collection of notes that Ron wrote to her, and a tattoo on her right forearm in his handwriting that reads I love you. Sometimes, the family will play a 17-year-old voice mail that Ron left for one of his co-workers, just to hear his once-commanding voice. “It carries several expletives,” Dawn says. “But it’s still good to listen to.”

There is nothing good about Ron Kirchner’s condition. But in exactly one way, Dawn feels fortunate: She can afford to personally care for her husband. The Kirchners have money saved. Ron’s pension and Social Security cover their expenses. Some of his former firehouse colleagues built the family a backyard deck and helped them get a hospital bed for Ron to sleep in at home. Luke and Ava live with their parents, which means Dawn usually can count on a helping hand. “If it wasn’t for my daughter, I’d never be able to take a shower,” she says.

Dementia care can be ruinously expensive. The median cost of a nonmedical home health aide is nearly $50,000 a year, while a private room in a nursing home is roughly $106,000. And even less severe cognitive impairment can make it hard to earn a living. Totaro, the retired New York City police officer, says that she scored highly on the memory portion of her academy exam. “I didn’t need a calendar,” she says. “I didn’t need a phone book.” She is now coping with memory loss. Totaro quit a job as a bank teller because she couldn’t keep numbers straight. She tried working at a fast-food restaurant. “They put me on the drive-through window and had to take me off immediately,” she says. “It was too much.”

John Feal hears similar stories. A construction worker who was seriously injured at Ground Zero in the days following 9/11 and has since become a leading advocate for responders, Feal gets phone calls and emails from worried spouses. My husband is deteriorating. He doesn’t remember anything. I think he has dementia. Every September, Feal organizes a ceremony at the granite memorial wall for people who died of illnesses related to 9/11 that he helped build in Nesconset, N.Y. “I see the same guys each year, and the physical and mental differences are so evident,” he says. “They are so macho and full of bravado that they will say otherwise. But they are not the same people.”

Working with other responders and former “Daily Show” host Jon Stewart, Feal was a driving force behind the James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act, a 2011 federal law that provides health care to 9/11 responders and survivors through the World Trade Center Health Program, as well as money through a victim compensation fund. To date, that fund has paid nearly $8.7 billion to about 40,000 sick or dying people, and the number of 9/11-related illnesses it covers has expanded over time.

But cognitive ailments are not among them. “As people become more and more impaired, they may need more and more care,” Clouston says. “But none of that is provided. You are on your own.” For that to change, as it did in 2012 when 50 types of cancer were added to the list of covered conditions, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and a special scientific advisory committee will need to see more and better evidence that what is happening to Ron Kirchner and others began on 9/11. That will require more research and more time. “To put a new condition on our list, you have to show that it is substantially likely to be causally related to [9/11] exposures,” says institute director and health program administrator John Howard. “That means we can’t explain it in any other way.”

A physician now serving his third term as the institute’s director, Howard was appointed by President George W. Bush to coordinate the earliest federal response to the health effects of 9/11 and has overseen the health program since its creation. He says the program is concerned about cognitive impairment among responders and eager for researchers to answer the questions surrounding it. “Without them,” Howard says, “we would be blind.”

Luft worries that the worst may be yet to come. Stony Brook’s studies cover a sliver of the total responder population. There could be thousands more with cognitive impairment, and hundreds more with dementia. Are they falling through the cracks? The group is aging, which places all of them at greater risk. “It’s terrifying,” Luft says. “Five to six years ago, [the responders] were at one level. And now they are worse. Five to six years from now, we don’t know exactly what it will look like. Some will level off. But some will be worse.”

When Ron was first becoming forgetful, Dawn would tape family photos to their kitchen cabinets. This is Ava, our daughter. This is Luke, our son. She would look her husband in the eyes and show him her wedding ring. “We’re married,” Dawn would say. “Oh!” Ron would respond, surprised but pleased. “That’s good.”

Sometimes, Ron still laughs when Ava makes funny voices. But it’s hard to know what he’s responding to, or why. For the Kirchners, 9/11 never really ended — and in the future, Dawn fears, her family will have company. “It’s not an official World Trade Center illness yet,” she says. “But it will be.”

This has been Hreal Sports, a weekly-ish newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. If you have any questions or feedback, contact me at my website, www.patrickhruby.net. And if you enjoyed this, please sign up and share with your friends.