The Longest Cons

Like athletes swindled by financial scammers, Republicans convinced that Donald Trump beat Joe Biden are having a hard time accepting that they’ve been duped. Why?

Welcome to Hreal Sports, a weekly-ish newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. Sign up and tell your friends!

Editor’s note: Some of the material in this article comes from reporting and writing I did for a Washington Post Magazine story about investment fraud lawyer Chase Carlson, which you should go read next. It’s a darn good story!

Chase Carlson brought receipts. Enough to fill a binder. A Miami-based investment fraud lawyer who specializes in representing professional athletes who have been swindled by crooked financial advisors, he was meeting at a coffeeshop with two National Football League players who had invested money with a man named Jinesh “Hodge” Brahmbhatt.

Brahmbhatt talked a good game. He told his athlete clients, mostly NFL and National Basketball League players, that he would create wealth for “their kids and grandchildren” through “ultraconservative” investments. Among those investments? Promissory notes purportedly delivering returns between 12 and 30 percent.

Carlson figured that was too good to be true: most low-risk investments, he knew, offered returns in the low single-digits. So he dug into Brahmbhatt’s business, and ultimately shared what he found with both the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (Finra), a nongovernmental organization that also oversees parts of the securities industry.

Finra later banned Brahmbhatt for life, determining that some of the promissory notes were bogus and part of a Ponzi scheme orchestrated by one of the advisor’s acquaintances. Similarly, the SEC fined Brahmbhatt nearly $1.6 million for failing to tell clients that his firm was receiving payments for peddling the notes.

Before Carlson tipped off regulators, however, he tried to warn athletes directly—including the two NFL players at the coffeeshop.

Working from a binder containing 14 exhibits, Carlson laid out his evidence. One of the companies offering the promissory notes had been fined by the Department of Justice for lying to obtain a federal contract. Brahmbhatt’s seemingly successful advisory company was loaded with debt, bringing in insufficient income, and owed more than $100,000 in unpaid state and federal taxes. Brahmbhatt previously had settled an arbitration case with a former NFL player who had accused him of mismanaging nearly $1 million. Brahmbhatt and two of his employees had even failed their financial licensing exams multiple times.

These are red flags, Carlson explained. You need to take a hard look at where your money is going. Before it’s too late.

One of the players listened intently. He seemed concerned. But the other player was dismissive—and defensive. “He actually tape-recorded me and sent it to Hodge,” Carlson says. “I got a letter from Hodge’s lawyer.”

The tape-recording, Carlson says, was unusual. But the rest? Not so much. Too often, Carlson says, athletes on the wrong end of financial scams have a hard time accepting that they’ve been hoodwinked. “I warned a bunch of athletes about Hodge, and a lot of them didn’t want to believe it,” he says. “I’ve seen a lot of guys get warned in other cases, and sometimes they don’t believe it.” Even when there are red flags, athletes can end up looking past them.

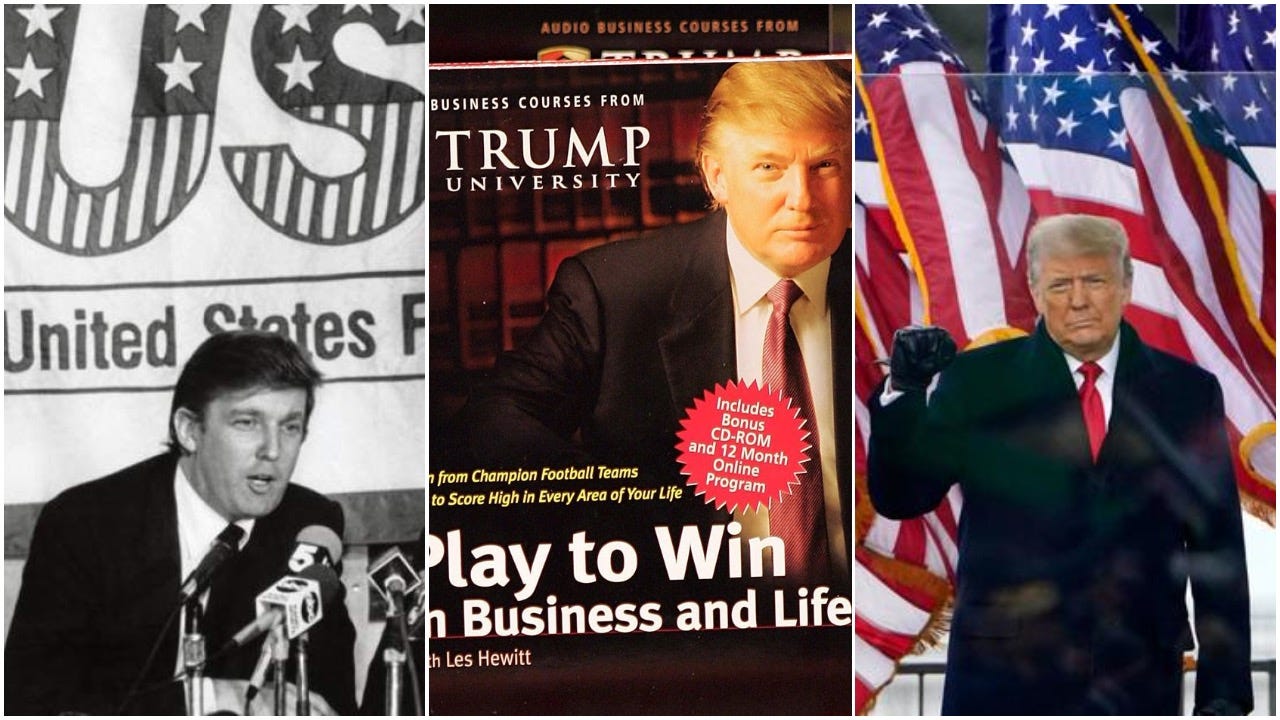

America has a problem. Tens of millions of people, almost all of them Republicans and/or pillow tycoons, have been conned. Like the athletes who placed their trust in Brahmbhatt, they’re in thrall to a big lie: that Donald Trump actually won an election that he very clearly lost, all because Joe Biden cheated.

Of course, there is no actual evidence that the 2020 presidential election was marred by widespread or outcome-changing fraud. Claims to the contrary have been disproven, debunked, and tossed out of courtrooms by nearly 90 judges. The primary proponents of those claims are Trump himself—a volume-shooting fabulist whose lifelong relationship with the truth is roughly akin to Galvatron’s relationship with Starscream—and Rudy Giuliani, a Fox News Cinematic Universe glue guy whose public pronouncements and public bouts of flatulence are increasingly indistinguishable.

Yet despite those red flags, large majorities of Republicans—between 65 and 77 percent, depending on the particular poll—believe that there was widespread voter fraud during the election, that Biden did not win the election legitimately, that Trump received more votes than Biden, and that the electoral process in the United States can’t be trusted.

None of this is great for American democracy! Trump’s con undermines the legitimacy of both the Biden administration and the federal government in general. It gives state-level Republican lawmakers even more motivation to disenfranchise Democratic-leaning voters with new voting regulations like eliminating at-will absentee balloting and tightening voter ID requirements. It led directly to the violent and deadly storming of the Capitol by a rioting mob of angry Trump superfans, all of whom were egged on by Trump and other GOP elected officials-cum-malarkey merchants, including Josh Hawley and Ted Cruz. And it leaves Republican voters like Daniel Scheerer, a 43-year-old truck driver in Colorado recently interviewed by the New York Times, contemplating some extremely stupid and dangerous shit:

“I can’t just sit back and say, ‘OK, I’ll just go back to watching football,’” said Scheerer, who went to the rally in Washington this month, but said he did not go inside the Capitol and had nothing to do with those who did. He said he did not condone those who were violent but believed that the news media had “totally skewed” the event, obscuring what he saw as the real story of the day — the people’s protest against election fraud.

“If we tolerate a fraudulent election, I believe we cease to have a republic,” he said. “We turn into a totalitarian state.”

Asked what would happen after Mr. Biden took office, Mr. Scheerer said, “That’s where every person has to soul search.”

He continued: “This just isn’t like a candidate that I didn’t want, but he won fair and square. There’s something different happening here. I believe it needs to be resisted and fought against.”

And:

“It’s way more than just being some kind of a Trump fanatic,” Scheerer said. He said he saw himself as “a guy up on the wall of a city seeing the enemy coming, and ringing the alarm bell.”

Force, he said, is only a last resort.

“Are you OK with internment camps if you refuse to wear a mask or take a vaccination?” he asked. “I believe in a world where force has to be used to stop evil or the wrong act.”

You can see where this is going: unless marks such as Scheerer realize en masse that they’ve been had, Trump’s stolen election story will continue to metastasize, causing more harm to the body politic for years to come. But is such a shift forthcoming? If the parallel experiences of hornswoggled athletes and other scam victims are a guide, then change is possible—and also far from guaranteed.

Anyone can be scammed. A 2018 report from the financial firm Ernst & Young estimated that from 2004 through 2017, athletes across all sports alleged fraud-related losses of nearly $500 million. (Carlson, who tracks cases on a spreadsheet of his own, believes the actual total exceeds $1 billion). In 2019, the Federal Trade Commission received nearly 1.7 million fraud complaints and reported that overall fraud losses were more than $1.9 billion.

To understand why cons solider on—even in the face of compelling contrary evidence—it helps to understand how people are snookered in the first place. In her 2016 book The Confidence Game: Why We Fall for It … Every Time, aptly-surnamed author Maria Konnikova uses interviews, anecdotes, and a whole lot of behavioral psychology to construct what amounts to a Grand Unified Theory of Scamming.

Con artists, she writes, are successful largely because we do most of their work for them.

Nobody sees themselves as a sucker. According to a study cited by Konnikova, about 95 percent of people think that they are better than average at judging other people’s trustworthiness. In reality, however, we’re exceedingly mediocre at discerning deception: researcher Paul Ekman has spent more than 50 years having over 15,000 subjects watch video clips of people either lying or telling the truth about a wide variety of topics. The success rate at identifying honesty? About 55 percent—slightly better than a coin flip.

More importantly, Konnikova writes, we all want something. Scammers suss that out, and present themselves as genies who can fulfill our deepest wishes. They bond with us by creating rapport and exploiting our empathy—becoming like us, or like the kinds of people we want to be around. In one psychological study cited by Konnikova that involved evaluating a series of altered head shots, participants judged the people in the photos to be more trustworthy the more similar to their own faces the pictures became.

Once trust has been established, Konnikova writes, con artists encourage us to feel instead of think. They persuade us by amplifying reasons to say yes and obscuring reasons to say no. They show us just enough evidence of an actual, legitimate payoff to make us believe that more (much more!) is on the way. And they seduce us with gripping stories that compel us to emotional and behavioral receptivity—the most successful commercials, researchers have found, are the ones with memorable narratives.

Our enemies are getting stronger and stronger by the day, and we as a country are getting weaker. The world is laughing at us. We need somebody that can take the brand of the United States and make it great again. I will be the greatest jobs president that God ever created. America will start winning again, winning like never before. We will bring back our jobs, bring back our borders, bring back our wealth and we will bring back our dreams. I will build a great wall, very inexpensively, and have Mexico pay for it. I am your voice. I alone can fix it.

Sound familiar?

While working with his clients, Carlson has seen this pattern play out over and over again. Athletes have relatively short careers. They want long-term financial security for themselves and their families. They know they need to invest, but don’t know how to go about it.

“There’s a big difference between being street smart—knowing that some things are too good to be true—and knowing how to vet financial investments,” Carlson says. “Most athletes wouldn’t know that a 12 percent promissory note is too good to be true. Most Americans wouldn’t know that. If you’re a couple years out of college or never took a finance class in the first place, how would you know that?”

When it comes to managing their money, athletes are looking for someone to trust. Scammers know how to fit the bill. Some, Carlson says, drive flashy cars, wear pricey watches, and throw big parties in bigger houses—all to project an image of success. I’ve made it. Work with me, and you can, too. “A lot of athletes are the first person in their family who really has money,” Carlson says. “So when they see an advisor living in a mansion, wearing really expensive suits, hanging out with all these other big-name athletes, that makes them seem credible.”

Others take the opposite approach. One advisor, I’ve heard, likes to throw a Bible in his bag and point it out when he’s meeting with religious athletes—even though the advisor isn’t religious himself. “A lot of these guys are chameleons,” Carlson says. “They will pretend to be who you want them to be. They bond with you, gain trust and loyalty with you, and manipulate you by telling you what you want to year.”

Aaron Parthemer, a South Florida-based adviser who worked with roughly 40 athletes before being barred by Finra and the SEC for misconduct that cost his clients millions, pitched himself as more than a financial sherpa. He was a friend. Former NFL player and Carlson client Antwan Barnes ultimately lost about $200,000 investing with Parthemer. “I signed with Aaron because he felt warm, like home,” Barnes says. “I felt like this guy’s not bulls—-ing me about anything. So I was mad, but more disappointed. I had grown to know Aaron over the years. I knew his mom and brother. I met his wife and kid. It felt like a betrayal of trust.”

The same factors that make cons compelling also make them sticky. By the time red flags start to appear, victims often are so emotionally invested in scammers—or in the tales they’re telling—that they look the other way.

In her book, Konnikova describes a 2006 study in which a computer program was able to detect fraudulent financial statements 85 percent of the time; by contrast, a group of professional human auditors who spot fraud for a living were only able to identify 45 percent of the bogus statements.

Why the vast gap? The auditors’ feelings got in the way:

When they found a potential discrepancy, they would often recall a case where there was a perfectly reasonable explanation for it, and would then apply it there as well. Their assumptions probably gave people the benefit of the doubt more generously than they should have. Most people don’t commit fraud, so chances are, this one isn’t, either.

Louis Delmas, a Carlson client who lost money with Parthemer, can relate. When Delmas was drafted by the Detroit Lions in 2009, he later told federal investigators, he wanted to “focus on football.” So Delmas went along with Parthemer’s suggestion that he invest in Club Play, a Miami Beach nightclub; he even let Parthemer decide the amount of money.

According to Delmas, Parthemer never offered to show him the club’s financial statements, which would have revealed roughly $3 million in losses over a three-year period. And Delmas never thought to ask for them. Nor did he think to question why Parthemer bought a boat to promote Club Play; why he fronted money for promotional expenses like securing a hotel room for Tommy Lee and Pamela Anderson when the Super Bowl was held in Miami in 2010; why he also worked on opening a strip club in Doral; why he pitched a pie-in-the-sky club-centric promotional tequila deal to Bacardi that cost Delmas and others even more money; and why he tried to create a club-affiliated Miami Bikini Team in order to, in Parthemer’s words, “meet girls,” according to depositions taken as part of investigations by regulators.

Delmas was stunned to learn from investigators that Parthemer had transferred $200,000 from his bank account into accounts connected to Club Play and the prospective strip club. Parthemer did “a great job of putting numbers together and making me happy,” Delmas told investigators, “knowing I don’t know where to go or I don’t know how to go about it, getting the truth out of this information.”

And even when scams are revealed, we struggle to accept—and admit—that we’ve been tricked. Konnikova writes that cons are chronically underreported. Why?

… to the end, the marks insist they haven’t been conned at all. Our memory is selective. When we feel that something was a personal failure, we dismiss it rather than learn from it. And so, many marks decide that they were merely victims of circumstance; they had never been taken for a fool.

In June 2014, a so-called suckers list of people who had fallen for multiple scams surfaced in England. The list had been passed on from shady group to shady group, sold to willing bidders, until law enforcement had gotten hold of its contents. It was 160,000 names long. When authorities began contacting some of the individuals on the list, they were met with surprising resistance. I’ve never been scammed, the victims insisted. You must have the wrong information.

Carlson has noticed a similar phenomenon among athletes who have been ripped off. Many keep quiet, eat their losses, and move on without calling the cops or filing lawsuits—all because they don’t want anyone to know they’ve been had. “The cool thing for athletes today is to portray the image that they are sophisticated investors,” he says. “If an article came out about how they got screwed on some investments, it would make them look unsophisticated.”

In some cases, scam victims respond to the walls closing in by doubling down. Psychologists call this the “sunk cost effect”: once we’ve invested heavily in something, we become less likely to see it clearly. We’re also loathe to cut our losses, because doing so would mean admitting a mistake. And that carries a heavy emotional price.

In one Northwestern University study of business schools students, Konnikova writes, researchers found that telling the students flat out that an investment decision was bad wasn’t enough to get them to reverse it. Instead, the students felt responsible for the investment and kept putting money into it—more than into any other option.

A few years ago, Carlson and his father Curtis—a longtime securities fraud litigator with his own practice—were meeting with a NFL player who had been a client of an advisor named Jeff Rubin, who was barred from the securities industry by regulators after 31 NFL players lost a combined $40 million investing in a failed Alabama electronic bingo casino that Rubin recommended and partially owned.

The player was looking for a lawyer. The Carlsons reviewed his financial statements. They broke the bad news: Your money is gone. You need to cut ties with your adviser.

I can’t, said the player, who subsequently hired other attorneys. He’s paying my mortgage.

“It didn’t sink in,” Curtis Carlson says. “He thought Rubin would keep paying.”

What makes reality sink in? For athletes, Chase Carlson says, the answer is usually pain. Loss. There is always a moment, he says, when his clients realize that their money is gone—and that there’s no way to explain it back into existence.

“Imagine you’ve invested in something like a Dunkin’ Donuts franchise and your advisor keeps telling you that it’s going good, even though you don’t see a dividend for years,” Carlson says. “At some point, you’re like, ‘what the f___? Where’s my dividend?’ You get fed up. Or one day, you get a bankruptcy notice for the franchise in the mail.

“That can take a long time. But these [scammers] can only BS for so long. Eventually, things get real.”

Things have gotten real for Trump. He’s no longer president. He has been impeached by the House for incitement of insurrection. He may have lost enough support among influential Republicans to be convicted by the Senate, an outcome that could prevent him from holding federal office ever again. He faces ongoing legal jeopardy on multiple fronts including tax evasion, election interference, and business fraud. GOP politicians and government officials who supported his efforts to overturn the election on the basis of pure fantasy could be in trouble, too. And Trump’s most fervent supporters—the ones who stormed the Capitol because they believed, like the Colorado truck driver Scheerer, that the election was fraudulent—already are facing consequences.

That’s the good news. The bad news? The vast majority of Republicans who have swallowed Trump’s nonsense—who are deeply invested in keeping the faith—are not paying a price for it. There is no missing dividend, no bankruptcy notice in the mail, no empty checking account. There’s no actual downside to believing that Biden cheated his way to the White House. To the contrary, there’s only emotional upside, an enormous shot in the arm to the deep feelings of victimhood that animate contemporary GOP politics, the perpetual sense of grievance that unites Evangelical Christians, reactionary billionaires, racially resentful Whites, and the rest of the Republican coalition with a narcissistic New York real estate failson whose lifelong lodestar has been stiffing, screwing, cheating, and hurting almost everyone he encounters, all while telling anyone who will listen how very unfair the world has been to him.

In her book, Konnikova tells the story of a man named David Sullivan, a cultural anthropologist turned private investigator who spent 20 years infiltrating cults. Sullivan, she writes, would learn the cults’ language, their customs and ways, and their views on life—because only as a “true believer” could he hope to talk to cult members and persuade them to leave.

Sullivan was very good at what he did. When working to extract cultists, he would show them receipts, proof that cult leaders were not the selfless and holy figures they portrayed themselves to be. “I have to show them that the money that went to the mission was actually spent on a second house, a mistress, a lavish lifestyle in LA,” Sullivan says in the book. “And the trip to visit the orphanage, well, here’s the receipt: they were in Vegas, gambling.”

Sometimes, this helped. But many times, it didn’t. Konnikova writes:

… as Sullivan frequently pointed out, physical evidence often didn’t even matter. Show it to those who’d already bought into the fiction, and many would say, “No, that’s impossible. I know this man; he’s a man of God. No way.” And even though Sullivan had seen the same dynamic play out dozens of times, it didn’t make it any less troubling or difficult to wrap his head around. “That still to this day sometimes stops me in my tracks.”

Scams, Carlson says, work a bit like stock prices. The numbers go up. The numbers go down. It’s easy to tell a convincing story explaining movement in either direction—because ultimately, you don’t register an actual gain or loss until you sell your shares. But what if you never have to? “Hypothetically,” he says, “that kind of con could go on forever.”

This has been Hreal Sports, a newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. If you have any questions or feedback, contact me at my website, www.patrickhruby.net. And if you enjoyed this, please sign up and share with your friends.