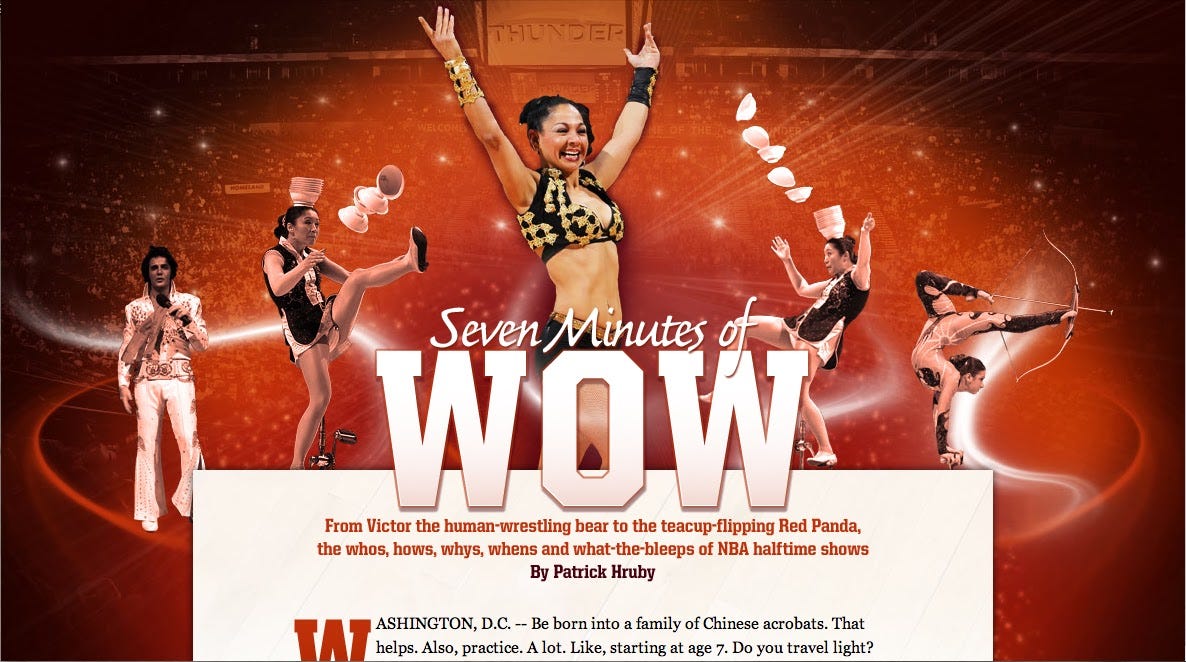

Seven Minutes of Wow

From Victor the human-wrestling bear to the teacup-flipping Red Panda, the whos, hows, whys, whens and what-the-bleeps of NBA halftime shows.

Welcome to Hreal Sports, a weekly-ish newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. Sign up and tell your friends!

Editor’s note: David Maas, NBA halftime show legend and half of the husband-wife magic act Quick Change, died on Sunday at age 57 of COVID-19. In 2011, I spent some behind-the-curtain time with David and his wife, Dania, for a feature piece I wrote about NBA halftime acts—the couple couldn’t have been more friendly or gracious, and to this day, the story stands as one of the most fun articles I’ve ever worked on. You can read it below, or if you’d prefer to experience its full ESPN glory while supporting a publication that supports yours truly, click here!

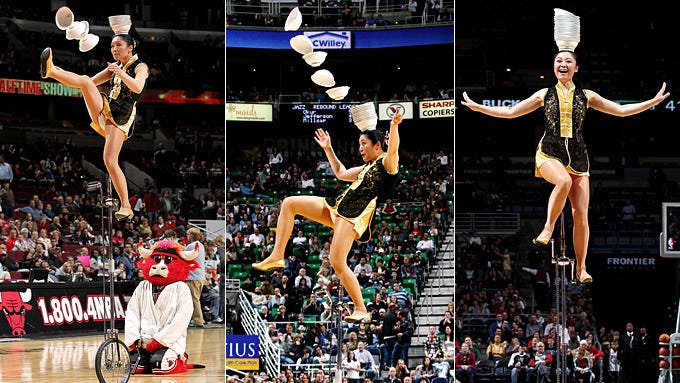

WASHINGTON, D.C. -- Be born into a family of Chinese acrobats. That helps. Also, practice. A lot. Like, starting at age 7. Do you travel light? Can you touch your toes? With your ears? Good. You just might make it as an NBA halftime act. Provided you can do something unique. Like placing five small bowls along your leg. Flipping them into the air. Catching them in a neat chimney stack atop your head. Teetering atop an 8-foot-high unicycle at the same time. Doing all of this in front of a packed arena. Knocking 'em dead.

Also, no drops.

Krystal Niu stands inside an entrance to the Verizon Center in D.C., just off a red-eye flight, two large carry-on bags in tow. A team intern approaches, blond and eager.

"Are you Red Panda?" asks the intern, who seems confused. Maybe she was expecting an actual bear. Professional basketball has seen stranger. Red Panda is Krystal's stage name. Red: the color of weddings, newborns and luck. Panda: the national animal of China, where Krystal grew up. Years ago, when she was new to America, a local suggested the moniker. Krystal was grateful. She didn't know what to call herself. Bowl-flipping girl? Who would pay to watch that?

"OK," says the intern. "Follow me. I'll show you to your locker room."

We walk down a long cinder block hall. Past an empty courtside club. Past a vacant press room. Past Washington Wizards guard John Wall, who looks as tall as Wilt Chamberlain next to Krystal. Past the visiting locker room, soon to be occupied by another traveling road show, LeBron James and the Miami Heat.

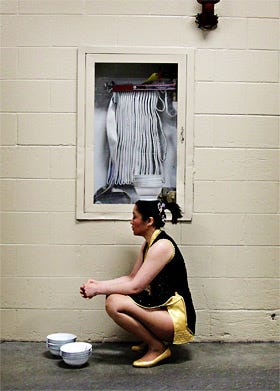

Krystal's bags roll behind us, clattering against the floor. Inside are a makeup compact, 16 plastic bowls, a traditional Chinese dress and a disassembled unicycle. Toothpaste, maybe. A white sheet of paper taped to a blue door reads HALFTIME ACT. The intern lets us in.

"So," she asks. "What is it, exactly, that you do?"

Good question. I'm wondering myself. This much I know: Krystal is a professional sports halftime performer, a foot soldier in the sideshow army of contortionists, Frisbee dogs and trampoline dunkers who make their livings by providing seven minutes of wow. On the NBA circuit, she's a cult celebrity. Fans ask for her. Players give her fist bumps. She has performed for the league in London and in China, outlasted Patrick Ewing on Broadway and Shaquille O'Neal in Hollywood. She does magic on the side. Her age is somewhere between 30 and 50. Also magic. Overhead bins act as her home away from home. She flew in from San Francisco; tomorrow, she heads to Portland, Maine; from there, Fort Wayne, Ind. Some towns, she knows people -- photographers, reporters, public address announcers. Most places, she doesn't. Sitting on a plane, marooned at a gate, she'll talk to anyone willing to listen. People think she's crazy.

Then she mentions her act.

What is it, exactly, that you do?

Krystal can't answer. Doesn't know how. She loves what she does. Never wants to stop. But to put it into words?

Usually, she just sends a DVD.

Actually, forget discs. Just go to YouTube. Enter the following words:

1. Amazing

2. Christopher

3. Halftime

Click on the first link for a University of Connecticut basketball game. You'll see this: an African-American man in a fringed black vest, black bikini briefs and a faux-Native American headdress, stomping and dancing around a basketball court to a medley of dated pop hits -- largely from the Village People's back catalog -- surrounded by four men dressed as other members of the Village People, the cop and the cowboy and the biker and the construction worker, only they're not actually men, but rather life-size human puppets, attached to headdress guy by an intricate system of large, linked poles, so man and puppets are moving as one, and now headdress guy is singing along, and giving a blatantly suggestive neck rub to the leather-clad biker puppet, and pantomiming "Y-M-C-A," and … well, that's it. The whole show. Five minutes and 25 seconds of your life that you are not getting back.

And yet, people are cheering.

Actually, not just cheering. Clapping along. They like the music. They love the headdress guy. His name is Christopher. He probably has a last name. It doesn't matter. Christopher lives in Las Vegas. He's one of the longest-running halftime acts around. He performs a second show that's basically the same except the puppets wear Michael Jackson costumes, and Christopher busts out a slippery moonwalk in homage to "Billie Jean."

That kills, too.

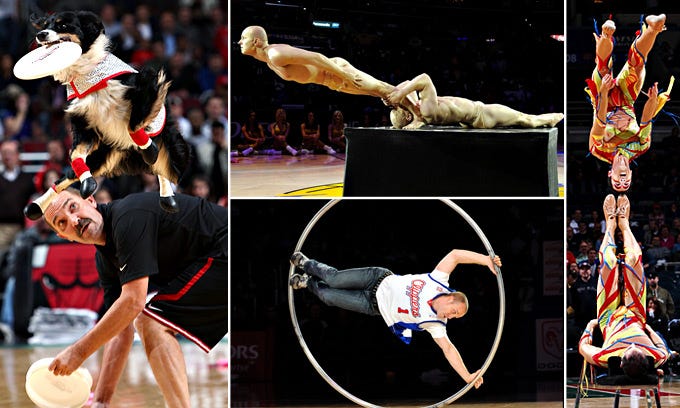

"An act has to be fresh," says Jon Terry, an Oklahoma-based booking agent for sports halftime performers. "Hit one of the senses. It needs to either be very funny, thrilling or totally bizarre."

On the floor, under the lights, you definitely need a shtick. Something to fill seven minutes. (Go a bit shorter for college games, halve the seven minutes for hockey intermissions.) Something the hoi polloi can see from the nosebleeds. Something that doesn't mess up the floor. (Sorry, equestrian lovers.) Something -- and this is key -- that grabs people in 30 seconds, max, because it's hard to bring down the house when half of the paying customers are standing in line for beer and/or the urinals.

"We always knew we had a good act when the merchandise and concession people would complain that their sales were worse," says Mike Chant, the NBA's director of live programming and entertainment, who used to book acts for the New York Knicks. "You're really just looking for the wow factor."

The wow factor is akin to former Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart's definition of pornography, or maybe "the Matrix." No one can describe it. You have to see if for yourself. Rubberboy has it. A contortionist billed as "the world's most flexible man," he can dislocate his arms and legs, the better to squeeze himself into a clear box the size of a medium suitcase. Rubberboy's real name is Daniel Browning Smith. He is 32 years old. He's currently on pro basketball hiatus, thanks to the recent arrival of a Rubberbaby. "After his show, people tell us he's disgusting," says Shelly Driggers, the Orlando Magic's director of arena and event presentation. "But they stay in their seats to watch."

Lilia Stepanova has it, too. She's cute. She's bubbly. She can handstand on canes while operating a bow and arrow with her feet. An NBA halftime regular, she once shot an apple off Jimmy Kimmel's head. She appeared on "America's Got Talent."

David Hasselhoff loved her.

Terry the booking agent has been working with sports performers for almost 20 years. He once represented Morganna the Kissing Bandit. He currently reps a human Slinky, a professional hula-hooper from the Moscow Circus and the world's shortest Elvis impersonator. (FYI: also an ordained minister, and available for weddings.) Terry considers himself a student of the art form. His appreciation is deep, and real. When auditioning potential performers, he keeps one thought in mind: Always be willing to believe that anyone can do anything.

One day, a young woman walked into Terry's office, a dog in tow. "My dog can talk," she said. Terry waited. And waited. For 15 minutes. The woman cajoled. Pleaded. The dog remained silent.

Another time, a man calling himself Mad Chad claimed he could juggle chainsaws. "Really?" Terry asked. "Then what's the trick?"

"Well," said Mad Chad, "it's not like I sharpen them or anything."

"Sure enough, he could juggle chainsaws!" Terry says. "I'm not looking for a formula. I try to avoid a formula. Take a circus act. They work, but you can't just be a juggler. You have to take the balls and bounce them off a large keyboard and play a song at the same time. With sparklers coming out of your butt."

Sparklers. Buttocks. Check. Anything else?

"Don't die on my gig. I've said that to a number of people."

Quit now. No joke. Pack up your sparklers. Rejoin the circus. Catch the next flight back to Las Vegas. You think you have the wow factor?

The wow factor is the easy part.

David Maas was driving. Dania, his wife, was in the passenger seat. Early morning, still dark, fog and snow. The couple was leaving a mid-Atlantic college town, heading for the airport. They had worked a campus basketball gig the previous night. Nothing unusual. Exce

pt for the overturned truck in the middle of the road.

David stomped on the brake pedal. Shifted into park. Yanked on the parking brake. The rental car went into a spin; when it was over, Dania needed 60 stitches in her right knee. Ten days later, they were once again performing.

After the show, no one asked Dania about her knee. Or the pain. They didn't even notice she was limping.

"They asked the same thing they always do," she recalls. "'How do you do it?'"

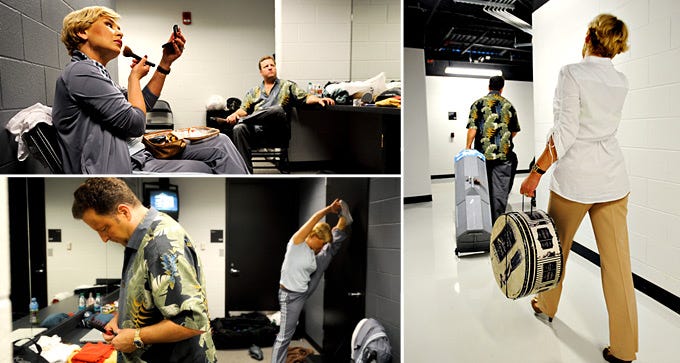

Together, David and Dania are Quick Change. They dance. They do magic tricks. They whip through a series of warp-speed costume switches. Like Lilia Stepanova, they've appeared on "America's Got Talent." (David famously told off Piers Morgan, who really had it coming.) They've also performed for Prince Charles and President George H.W. Bush. Together, 48-year-old David and 45-year-old Dania are the most successful halftime act in sports.

Another early morning. An airport gate in Dallas. David and Dania are waiting to board a flight to San Antonio. Four days ago, they were taping a television show in Italy; two days ago, they were trudging through snow in their home city of Chicago; last night, they appeared at a Dallas Mavericks playoff game; tonight, they'll perform for the Spurs.

David is blunt and detail-oriented. If a locker room has a television, he'll put on "60 Minutes." He looks a little like John Goodman, only thinner and more handsome. He has a leather satchel. This is his office. He's reading email, contemplating an invitation to perform on a Czech variety show. Dania is warmer, more empathetic, speaks with a Russian accent. She prefers "Entertainment Tonight." She sits on a cot, bleary-eyed, thumbing through photos on a digital camera. Here is Quick Change in Philly. In Japan. In Florida, at a New Year's Eve party hosted by Donald Trump.

"The first seven years we were married, we did not have one full week off," Dania says.

"Ever," David adds, looking up from his phone.

David and Dania have been married for 15 years. They met at a circus in 1995. Dania did a hula hoop act. David had graduated from riding in the Motorcycle Globe of Death -- don't ask -- to being a singing ringmaster. The two fell in love, but they had a problem.

"Our relationship couldn't work if I was on the road 200 days a year," David says.

Solution: Be on the road together. Create a two-person act. For a year, David and Dania studied costume change magic, all the way back to a 19th-century Italian vaudeville star named Fregoli. They rehearsed in secret, filming themselves and making adjustments. They trained with famed ballroom dance coach Bruno Collins. They bought pricey magic props, such as a $3,500 disappearing sunflower bouquet. They traveled to New York to find costume fabric. Money was tight. The couple was taking a risk: Fail, and the two could spend their career stuck on cruise ships.

"We had no idea the NBA would just explode," David says.

In 1996, David and Dania made their pro basketball debut at Seattle's KeyArena. They have since worked college basketball, the NHL, the NFL and for every NBA team save the Heat, who do not hire acts. They designed magic costumes for pop singer Katy Perry's concert tour and nearly did the same for Mavericks owner Mark Cuban during his stint on "Dancing with the Stars." (Costume changes were ruled illegal.) Like other top-tier halftime acts, David and Dania are paid $2,000-$3,000 per NBA performance. It's a good living, and a transient life. Including travel, typical workdays last 18 hours; during basketball season, the couple is on the road at least four days a week.

The trick, Dania says, is to pack earplugs. And two blankets. "People look at me funny," she says. "I sleep on the floor of airports. I sleep everywhere."

"It's hard," David says. "You're tired a lot."

"We pretty much know everyone who works at O'Hare [International Airport]," Dania says. "My bag is 50 pounds. Exactly. David is not allowed to pack too many socks or underwear."

"I hate airport security with a passion," David says. "They see the magic hat, the magic stuff. Bingo. They tear it apart. 'For your security, sir.'"

"You cannot call in sick," Dania says. "If you call in with a cold, the team won't call you the next time."

"The call can come at any time," David says. "Especially during the playoffs."

"Sometimes, we come home and my son is sleeping," Dania says. "Then we leave in the a.m. and he is still sleeping."

Woody Allen famously said that 80 percent of success in life is simply showing up. For NBA halftime acts, it's more like 50 percent. On the floor, performers have to surprise and delight; off the floor, they need to be as reliably dull as corporate lawyers. David and Dania fit the bill. They're professional. Polished. Take their work seriously. Teams know what they're getting. No headaches. No surprises. How do they do it?

They hustle.

Halftime at San Antonio's AT&T Center. The house lights dim. The spotlights come up. David and Dania are at midcourt. He wears a black tuxedo. She wears a blue ballroom gown. I'm standing on the baseline next to Chuck, the arena hype guy.

"I want to figure it out," Chuck says. "She's got a hump in her back. It looks like there's something under there." The show begins. Dania's in a red dress with feathers. A yellow-and-black dress that brings to mind a bumblebee. A green dress with fringes. After each switch, the crowd cheers a little louder; when David's suit unexpectedly transmogrifies into a Tim Duncan jersey, the place erupts. Chuck the hype guy grins. "He probably did that with the Mavericks last night, didn't he?"

Pretty much. Last night was a Dirk Nowitzki jersey.

Still in? OK. You'll need a résumé. Not some stupid, extra-thick piece of paper with bullet points and an over-considered font. The sum total of your entire life. No one grows up dreaming of becoming a sports halftime act.

But nobody just becomes one, either.

Back in the Verizon Center locker room, Krystal takes a deep breath, balancing a bowl atop her head. She's wearing her black-and-gold dress. Her makeup is done. Her assembled unicycle leans against a wall. The Wizards-Heat game is well under way. Radio play-by-play drifts in from an overhead speaker.

"Reverse layup for Miami. No!"

Krystal places a second bowl on her right foot. A third on her shin. A fourth just above it. This is practice. She kicks. The bowls cartwheel through space, landing one after the other inside the first. Clang-clang-clang!

"Sorry," she says. "I am going to make some noise."

Krystal has been making noise for as long as she can remember. She was born in Taiyuan, a mining and steel city in northern China. Her parents were acrobats, fourth generation on her mother's side. One day, when Krystal was a little girl, mom asked daughter what she wanted to be when she grew up.

"A dancer," Krystal said.

"How about an acrobat," her mom replied.

In circus families, there's a saying: born in a trunk. Remember Lilia Stepanova, the Human Bow and Arrow? Her parents were contortionists. Or take Quick Change: Dania's family worked in the Moscow Circus -- at one point training bears -- and David's father was a concert pianist who wrote music for Ringling Brothers.

Krystal began training at age 7. Her father taught her to balance a bowl atop her head, to hold another on her foot, to ride a series of increasingly tall unicycles, to do it all at once. Krystal fell. A lot. Dad was there to catch her. She was lucky. She saw other children break bones. By age 9, she was enrolled in a special, government-funded boarding school for traditional Chinese arts, practicing six days a week, seven hours a day. The work was hard. Boring. She started with 50 classmates. She graduated with 15.

By age 11, Krystal was performing throughout China. Five years later, she was invited to join the prestigious Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe. "It's like the NBA of acrobats," she says. "That's when I started traveling around the world." Krystal went to Australia, Europe and South Africa. She trained by day, performed at night, went out and partied afterward. The troupe was tight. Life was good, but Krystal wanted more. In 1990, she turned down a job offer in Japan and moved to the United States. Arriving just before Christmas, she knew no one. Barely spoke English. Had exactly one skill.

Still, she believed that anyone could do anything.

"I was thinking to take a chance," she says. "I didn't know what would happen. People thought I was brave. I didn't see it that way. I was young."

Krystal settled in San Francisco. Needing a place to practice, she found a local church that let her use a spare room. Grateful, she put on a free show. The congregation had never seen anything like it. Soon, she was performing for schools and hospitals, parties and other churches. A talent scout spotted her at a Chinese New Year's parade. She spent 18 months working at Disney World in Orlando. Her younger sister, Yu, joined her, then quit to become an accountant.

Krystal returned to the Bay Area. A friend suggested sports halftime shows. She sent her demo tape to an agent. He was dubious, wasn't sure a bowl-flipping act would connect with basketball fans.

On Thanksgiving in 1993, Krystal's phone rang. It was the same agent. He had booked a bicycle stunt act for the Los Angeles Clippers. Something had gone awry with their flight. Could Krystal hop on the next plane to LAX?

"That night, I got a standing ovation," she recalls of her first performance. "Four times. From that time, I mainly do sporting events."

One more warm-up flip -- five bowls. Krystal extends her arms, closes her eyes, imagines each bowl landing in its proper place. As a child, she found practice tedious; today, she gets antsy if she misses a day.

The radio announcer raises his voice: "Wade almost looks like a figure skater when he puts on those moves!"

She kicks. Clang-clang-clang-clang-clang! Perfect.

"It looks like he doesn't miss anything!"

Krystal smiles. She likes to be perfect. A dropped bowl makes her heart sink. Halftime is near. She pulls on her sweater. I ask one more question: "Have you ever considered doing something else, like your sister?"

I'm holding a pen. Krystal is holding a unicycle. She looks at me as if I'm the crazy one.

His name was Victor. He was an actual bear, trained to wrestle with actual humans. If you want to understand why NBA teams bother with halftime acts in the first place, man vs. ursine grapplin' is a good place to start.

Go back to the early 1980s. Pac-Man starred in a Saturday morning cartoon. Rocky Balboa had yet to win the Cold War. The NBA was slouching toward irrelevance, its playoff games appearing on network television via tape delay. To survive and grow, the league needed more than Magic Johnson and Larry Bird. It needed to reach families, children, couples on date nights, a casual audience beyond hard-core hoops junkies. Forward-thinking teams stopped selling basketball. They started selling entertainment -- amped-up music, mascots and dance teams, halftime shows.

Only whom and what to book?

Baseball had a long and successful/disastrous history of value-added entertainment, from barnstorming ballpark clown Max Patkin to oddball promotions such as Disco Demolition Night. (July 12, 1979: The Chicago White Sox use explosives to blow up a crate filled with disco records, setting off a riot at Comiskey Park.) But pro basketball? Not so much. Everything was new. And Detroit Pistons executive Dan Hauser was present at the creation.

Hauser started as a Pistons intern in 1978, working in an office of a half-dozen people, selling tickets to see a 30-win squad coached by Dick Vitale. A few years later, he was given a less daunting task: finding Silverdome halftime acts. He brought in a chainsaw juggler. A guy who tossed flaming swords. A pair of sumo wrestlers -- the real thing, not two morning DJs in foam fat suits. A group of lasso-spinning rodeo cowboys. Hauser held a pizza-eating contest before Kobayashi made competitive scarfing cool; he staged a tug-of-war between local firefighters and auto workers that ended with an exhausted man receiving first aid, right there on the floor.

Nobody told Hauser to stop.

He paid acts $150 a pop. He had a blast, largely because he never knew what to expect. One night, Hauser hired portly pool hustler Rudolf Walter Wanderone -- the self-proclaimed inspiration for fictional character Minnesota Fats, played by Jackie Gleason in "The Hustler" -- to put on an exhibition at half court. Wanderone was magnificent. He bombed. No one in the building could see what he was doing. But Victor the Bear, who once pinned four consecutive opponents during halftime of a game in Philadelphia?

The bear killed. Every time.

"We had a tarp that we would put on the middle of the court," says Hauser, now a Pistons vice president and the third-longest-tenured front-office employee in the NBA. "It was like a boxing ring."

"So the bear was roped off?"

"Oh, no. There was no ring."

"Then what?"

"Then the bear would wrestle against a local media person."

"Wasn't that dangerous?"

"You know, we didn't harm the bear at all."

Told about Victor, Chicago Bulls director of game operations Jeff Wohlschlaeger laughs. "We have dogs all the time," he says. "We could never have a bear." It's a game night at Chicago's United Center, a few hours before tipoff. The Atlanta Hawks are in town for the playoffs. The Bulls are on the court, shooting around. Also on the floor are a dozen fat guys, clad in T-shirts and sweatpants, rehearsing a dance routine. They are led by a midget. A choreographer gives directions, teetering on her six-inch heels. These are the Matadors, the comic doppelgangers for Chicago's primary dance squad, the Luvabulls, a traditional pompom-and-derriere-shaking outfit that is decidedly more: A) female; B) scantily clad; C) waistline advantaged.

Above, a block letter sign reads: "Welcome to the Madhouse." The arena itself glows and flickers like a slot machine in a Tokyo arcade: house lights, spotlights, laser lights, animated electronic admonishments to MAKE NOISE, billboards for Oprah Winfrey and Cirque du Soleil. The in-house sound system speakers can produce 50,000 audio watts. Later, there will be fireworks. Wohlschlaeger stands behind the scorer's table, a walkie-talkie jammed in his pocket, a beige courtside phone pressed to his ear. Overseeing a staff of about 75 people, he's the ringmaster/air traffic controller for every attraction in the building, from the magicians and palm readers on the concourse to the inflatable, prize-dropping cartoon bull blimp idling in the rafters.

"Look at Las Vegas," he says. "That is the ultimate model."

Blond and clean-cut, Wohlschlaeger has the reassuring mien of a local news anchor. He wears a red tie and a crisp gray suit. Two summers ago, he gave a marketing presentation to a group of college sports administrators entitled "creating the wow." This fits. Sixty minutes before tipoff, he huddles with his staff in a storage room, sidestepping people carrying giant bundles of balloons, rehearsing a two-page game script.

Pregame: Bulls guard Derrick Rose will receive the league MVP award. Check. Halftime: Acrobat Cassie Sandou will perform while hanging from a pair of red silks attached to the arena scoreboard. Check. First quarter, second television timeout: One of the Matadors, Dancing Mike, will appear on the Fan Cam, a ringer, strumming air guitar while singing along to Journey's "Any Way You Want It." Wohlschlaeger got the idea from the Los Angeles Dodgers.

"Remember to turn your hat around and point while singing," he says. "Just like we talked about. Got it?"

Dancing Mike nods. Wohlschlaeger scans the room. "Now, we just need a red hat."

Like contemporary Vegas, today's NBA is less "Gong Show" than Ivy League business school case study, a fine-tuned delivery system for market-tested diversion. No detail is too minute. Teams share ideas and best practices. Boredom is not an option. "The goal," Wohlschlaeger says, "is to make the outcome of the game as moot as possible."

Opening tip. Players from the Bulls and Hawks exchange fist pounds. Pregame pyrotechnics leave a smoky haze. During the second TV timeout, the Fan Cam cuts to Dancing Mike. He points to his hat, right on cue. This is the world Victor the Bear helped create, entertainment uber alles, an entire league as halftime show -- perfectly packaged, every moment a carnival. Only the basketball is left to chance. As Dancing Mike continues to faux rock out, it's hard not to wonder: If an actual bear were lip-syncing to Steve Perry, would anyone be surprised?

Krystal crouches in a Verizon Center stadium tunnel, just off the court. We are deep in the sports entertainment sausage factory. A guy on stilts ambles by, a mini basketball hoop draped over his chest. He gives her a silent nod. Next comes former Wizards center Gheorghe Muresan, no stilts required. Glad-handing with fans, he looks right past us. Muresan once starred in a forgettable movie with Billy Crystal, the same actor who once hired Krystal to perform at a birthday party.

Somehow, this makes perfect sense.

Krystal rocks back and forth. She cracks her knuckles. Rolls her head. Rubs her forearms. She scrapes her bowls along the concrete floor in small circles, then polishes them with a small cloth. After all these years, she still gets nervous. Every time.

"This is when I calm down a little," she says. "Or try to. It's not only if I miss or make it. It's the whole thing."

So much can go wrong. During last year's playoffs, Krystal dropped a bowl in Boston. She finished her act, but felt horrible. Even now, she throws up her hands, shaking her head at the memory. Friends say she's too hard on herself. Like a figure skater, she wants to be perfect. Two years ago, the Oklahoma City Thunder hosted Kristen Johnson, a professional escape artist. Handcuffed around her wrists and ankles, she was dropped into a narrow, water-filled tank. She suffered a hypoxic seizure -- caused by lack of oxygen to her brain -- and nearly drowned. Once, in Cleveland, baggage handlers damaged Krystal's unicycle wheel. When she started her routine, she didn't notice. She flipped her first bowl. Fans cheered. Everything felt fine. Then she attempted to change directions.

"I jumped off," she recalls. "I should say fell off, because the unicycle wouldn't turn."

Like stand-up comedians, halftime acts have an opponent. Us. The crowd. We can be drunk. Surly. Downright hostile if the home team is having a terrible first half. Quick Change once performed at a Denver Broncos game. Then-Broncos quarterback Brian Griese was struggling. David and Dania sat in a golf cart, waiting to drive onto the field. She sensed the discontent. Her hands were shaking. A fan noticed David's outfit. Hey, magic man! Can you make [expletive] Griese disappear?

"That happened a lot when I was at [Madison Square] Garden," says Chant, the former Knicks game operations director. "The halftime act comes on 60 seconds after the teams come off the court. The fans let it out on them."

On the floor, Wizards guard Jordan Crawford picks up a technical foul. The fans let it out on him. A mascot sprints past with a box of burritos. "Two minutes," the stadium announcer says. Krystal moves courtside. She slips off her shoes, stretches her toes. Miami leads by 10, a once-close game getting out of hand. Bad energy. A prize-dropping blimp hovers above, blotting out the klieg lights like a sudden solar eclipse. Krystal hands her unicycle to Terrance, a member of the Wizards' hype squad, the brave men and women who otherwise man the T-shirt-shooting CO2 cannons.

A mildly inebriated fan leans over the bleacher railing. "Are you going to ride that?"

"They don't pay me enough!" Terrance shouts back.

Halftime. The players come off the floor, followed by fans, a flash flood of bodies. Krystal vanishes. She reappears on the floor atop a metal ladder, clambers onto her unicycle. Terrance holds her bowls.

"Hold on to your seats!" says the PA announcer. "Watch in amazement as she performs her world-famous Guinness World Record act."

In a way, the players have it easy: Their only job is to give spectators what they want -- points, wins. But halftime performers? Their mission is akin to the one Steve Jobs put forth for Apple Computer: Give people something they don't even know they want. That is, until you show it to them.

On comes Krystal's music, a traditional Chinese wedding song. She was married, once. Not happily. Performing and travel were her escapes, a way to run from her problems, a way to cope. Eventually, she divorced. She cried often, sometimes could hardly talk. She spent time in China. She stopped performing for 11 months. But teams kept calling. Her first night back was in Washington, a spring evening, much like tonight. The cherry blossoms were in bloom. Right away, she knew: Something was different. She felt happier. Like herself again, younger and stronger and carefree.

"Just joy," she recalls.

Krystal flips one bowl. A small gasp. She flips two. Louder cheers. She flips three. Oooooooooh! People stop in the aisles. They stare. A father and son stand up from their padded courtside seats, transfixed. Krystal beams. Her joy is obvious, contagious, hard to explain.

Steve Max understands. A frequent NBA halftime performer and professional Simon Says caller from New York, Max was flying to Orlando, booked for a Magic game, sitting next to a woman. The plane landed. Passengers clapped. The woman made a weird face. She turned to Max.

"Don't you just hate it when people clap?" she asked. "The pilot is just doing his job. Do people clap at your job?"

"As a matter of fact," Max replied, "they do."

Four bowls. Still perfect. More clapping. The crowd is on its feet. Krystal rides to the far end of the floor, in front of the Wizards' bench. She holds five bowls aloft. One by one, she stacks them along her right foot and shin, all the way to her knee. Out go her arms. She holds the pose. Three seconds … five … 10. Behind me, two guys in embroidered dress shirts nearly spit out their beer. "Unbelievable!" they sputter.

What, exactly, does Krystal do? She flips plastic rice bowls onto her head while riding a tall unicycle. For a living. For her life. In a few minutes, she'll be forgotten, replaced by tall men throwing an orange ball through a red hoop. This is the normal order of things. And yet, if E.T. touched down at an NBA game, he would have a tough time ascertaining which act was the sideshow. Because the only difference between Krystal and John Wall -- between a Red Panda and a Washington Wizard -- is the meaning we ascribe to sports. The scorekeeping. The storylines. The ginned-up dramatic tension. The narratives we write and create. Krystal's performance is unmediated. So is her joy. You really have to see it. She can't put it into words. Doing so would defeat the whole purpose.

Last flip. Krystal closes her eyes. Photographers snap pictures. Fans watch open-mouthed. The bowls are aloft.

Clang-clang-clang-clang-clang!

She sticks it. Her eyebrows raise like a drawbridge. Her lips form an "O." The crowd follows suit. OOOOOOOOH! The beer guys lose what's left of their minds: "Dude, that's impossible!" Krystal leaps off her unicycle. Takes a stage bow in four directions. Runs off the floor. Her seven minutes are up. In the tunnel, she chats with a friend, a former Clippers scout. She gives Terrance a hug. Recently, her parents moved to America. They went to see her act. Krystal's father even held the bowls, the same way he did long ago. Mom and Dad were proud. They took it all in. The sights. The sounds. The people. There was just one thing they didn't understand.

Why were all these crazy Americans so excited for basketball?

This has been Hreal Sports, a weekly-ish newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. If you have any questions or feedback, contact me at my website, www.patrickhruby.net. And if you enjoyed this, please sign up and share with your friends.