Global Sport Matters: The Sports Gambling Issue

Sports betting in the U.S. has gone from illegal and taboo to an all-in gold rush. What does this shift mean for government finances, competitive and journalistic integrity, and public health?

Welcome to Hreal Sports, a newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. Sign up and tell your friends!

If you follow my work—a pretty safe bet if you’re reading this newsletter!—then you may have noticed that I haven’t written a whole lot over the last year. Well, there are two good reasons for that:

My corporate communications clients have kept me busy, which has been terrific for my personal bottom line, if not for the timely production of Hreal Sports content;

I’ve been steadily expanding my editorial role at Global Sport Matters, where I’m now editor-at-large.

Let me share a bit about the latter. It’s exciting! Global Sport Matters is the digital publication of the Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University. We cover a wide range of outside the lines, sports and society topics—including the ongoing lack of diversity among NFL head coaches—though original research and reporting, and via podcasts, live events, monthly themed issues, and standalone articles.

So where do I fit in? Almost everywhere. In my growing role, I’m responsible for coming up with issue themes and researching story ideas, finding writers and assigning stories, editing those stories, reporting and writing stories of my own, getting our content in front of people who might want to see it, and lots of other behind-the-scenes management and planning stuff.

It’s a lot. And to be totally honest, I’m still learning how to do it, juggle it, and excel at it. Still, it’s a terrific opportunity: a chance to help shape and build a publication from almost the ground up, with a mission of telling interesting and well-informed stories about the kinds of topics I care about. We don’t need to chase traffic or satisfy advertisers; instead, we’re focused on making things that leave readers and listeners better informed—and hopefully a bit entertained, too. It’s a wonderful luxury!

Moreover, it’s an opportunity for me to share everything I’ve learned over the last 20-plus years about reporting and writing with our contributors, all so I can help them and their work shine. Having spent far too much time stressing over each and every word in my own stories while navigating an extremely turbulent journalism industry, that is also a wonderful luxury.

(Note: this is where I mention that I’m always looking for new GSM writers and contributors—journalists, academics, anyone with a good and important story to tell. If that’s you, get in touch!)

Anyway, I’m telling you this so you understand what I’m up to, and what to expect from Hreal Sports going forward. I’ll still be writing, just not as frequently as in the past—and I’ll still share that work with you here, whether it’s for GSM, other publications, or the occasional Hreal Sports original. I’ll also be sharing GSM work with you. Sometimes, that will be standalone pieces by other writers; sometimes, that will be overviews of our monthly themed issues.

I hope you’ll continue to support, share, and engage with the work I’m doing. And I really hope you’ll continue to find it worthwhile.

Speaking of GSM’s monthly issues, our January edition is all about sports gambling. You can read the whole thing here.

Since a 2018 Supreme Court decision overturned a federal ban in states outside of Nevada, sports betting gone from mostly illegal and largely taboo to widely embraced and increasingly pervasive. Yet as states, leagues, and fans all join a multibillion-dollar gold rush, there are questions about the effect of this shift on government finances, competitive and journalistic integrity, and public health.

Our story package—and concurrent original national public opinion poll—is built around answering these questions. Spoiler alert: the answers are all incomplete, because we’re still in the early days of America’s sports gambling transformation.

That said, I think our pieces, summarized and linked below, are very much worth your time. The issues they address are only going to become more relevant over time, and I think you’ll see them pop up again and again and again as sports betting becomes increasingly indistinguishable from the American experience of sports.

“Tax Money From Sports Betting May Not Be the Windfall States Are Expecting,” by Neil deMause.

As sports betting becomes more popular across the U.S., local legislators often operate under the assumption that they will be taxing previously under-the-table transactions, generating new tax revenue streams in the process. But peeling back the layers shows that this money can be evasive and sometimes damaging to the local economy:

Whether that money should be considered a windfall or not depends heavily on what you think Garden Staters would have done with that money if not for legalized sports betting. If they otherwise would have spent the same amount placing illegal bets, that’s fresh money much as cannabis legalization has allowed states to tax economic activity that would otherwise be off the official books. But if legalization ends up cannibalizing other local spending that was previously taxed – known in economics as the “substitution effect,” because one form of spending is substituted for another – that could cause state tax revenues to go down.

“The substitution effect is a real thing,” says Matheson. “As you have more different types of gambling coming in, the question is: Is that new revenue for the state, or does it just mean you’re making less money from this other kind of gambling you have?”

One of the journal articles edited by Matheson provided a clue to just how much new forms of sports gambling can cannibalize older betting habits. West Virginia University economist Brad Humphreys looked at gambling spending in his state after it legalized sports betting in 2018, and he found that it brought in $2.6 million in new revenue in the first 18 months after legalization – but at the same time, the state coffers lost $45.4 million in taxes from video slot machines, which plummeted over the same period.

“Sports Gambling and Match-Fixing: What America Can Learn from International Soccer,” by Leander Schaerlaeckens.

While the dawn of sports betting has felt sudden in the U.S., stories from foreign sports leagues show that when gambling becomes pervasive, so too does match-fixing and other criminal action centered on sports wagers.

In 2013, former Croatian soccer player Mario Čižmek, who had been banned from the sport for life for match-fixing, told a conference that he had only resorted to taking bribes because his club had stopped paying him and he ran out of money. "I and the other players had not been paid a regular salary for 14 months, and I owed money on taxes and my pension,” Čižmek said. “We had no money, and we no longer spoke about training or football, but only about how we were going to survive.”

In many cases of corruption among players, the primary driver is financial need, not greed. The less a player earns, the likelier the player is to have trouble making ends meet, especially if they suffer a personal financial shock or crisis. In turn, that makes the player more susceptible to the advances of someone who promises to make problems go away.

This vulnerability is at the core of Hill’s equation for assessing the risk of a game being corrupted: total money gambled divided by median salary. And it ought to sound alarms for American college sports, which historically have been home to many high-profile fixing and point-shaving schemes, including scandals involving the City College of New York in the early 1950s and Arizona State University in the mid-1990s.

Americans love wagering on college sports. In 2018, the American Gaming Association estimated that more than $10 billion was wagered on the NCAA Tournament that year. And beyond athletic scholarships and small cost-of-living stipends, college athletes are unpaid. The math is the math: When Hill and co-authors Chris Rasmussen, Michele Vittorio and David Myers applied Hill’s equation to the major American sports leagues for an academic paper published in the Sport and Society journal in late 2020, they found that college football, basketball, and baseball, respectively, were the three American sports divisions most prone to corruption. (The next four, in order: the NFL, MLB, NBA, and National Hockey League.)

“The [National Collegiate Athletic Association] has a systemic problem,” Hill says. “If you were designing a league to encourage corruption, you couldn’t do any better than the NCAA, where the relative exploitation is so large. You have multimillion-dollar salaried coaches and officials and a league generating billions of dollars in marketing, TV, and image rights, and very little of that flows to the athletes.”

“What Happens to Sports Media When Everyone’s a Gambler?” by Brian Moritz.

Dozens of U.S. states have legalized sports betting, and the practice is pervasive in every aspect of sports coverage and consumption. But the people who report on sports face clear conflicts of interest as they navigate this new era.

Tim Graham offered a hypothetical situation.

Let’s say you are a sports journalist who covers the Montana State University men’s basketball team. They play in the Big Sky Conference – a long way from the bright lights of the Atlantic Coast Conference or the Big Ten.

You’re watching practice one day, the only media member there, and you see Montana State’s starting point guard turn his ankle. It’s clear he’s injured.

You open your phone. You see two apps next to each other. One is for Twitter, where you can publish the fact that the player is injured. The other is for a sports gambling website.

At the moment, you have information no one outside of that gym has.

“You can place a bet and take the points on Idaho State because you know he’s not going to play,” said Graham, a sports writer for The Athletic.

Is that OK? Is that ethical? As a journalist, what do you do?

“How America Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Sports Betting,” by Michael Weinreb.

States brought in billions in gambling revenues in 2021, and sportsbooks are becoming some of the most powerful properties in sports. How did America go from seeing gambling as an ugly vice to enthusiastically embracing it?

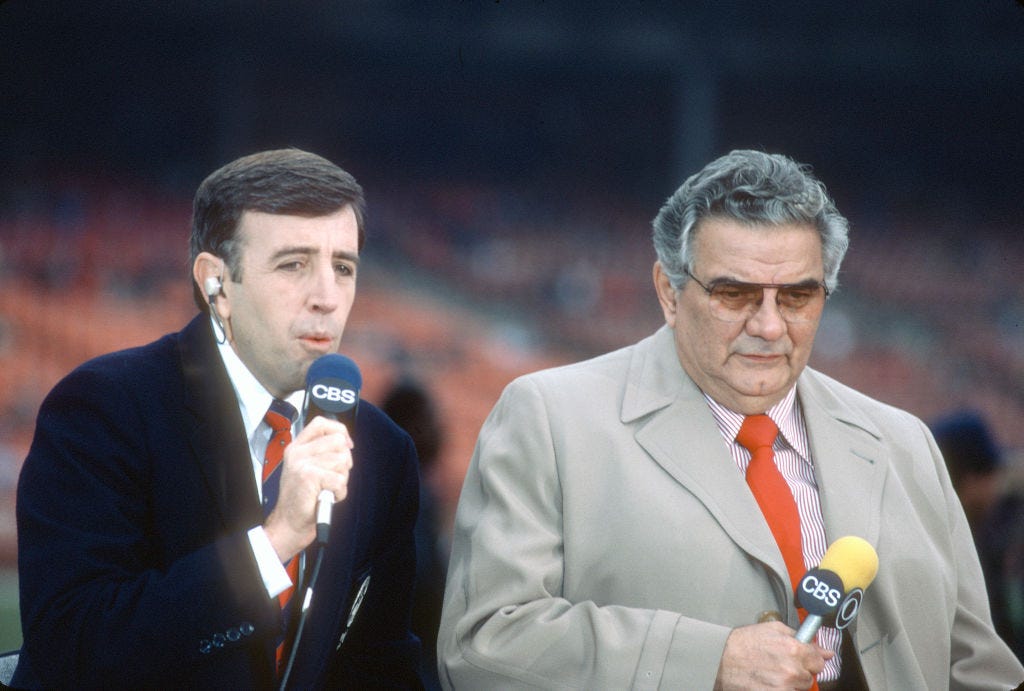

Before I can even bring up the comparison, Brian Musburger does it for me. “There are a lot of similarities with marijuana, in that for a large portion of the population participating in this market, there was a policy that people were tired of,” he says. “People that grew up in the ’60s and ’70s and ’80s had done these things, and the world wasn’t falling apart.”

Musburger saw this happening with sports gambling before many others did, in part due to his uncle Brett’s legacy and in part due to what he saw after spending time as an agent, working for his father, Todd. Internet culture was ascendant, which allowed people around the world to see what was happening in other parts of the world. In Europe, where gambling had long been sanctioned, there were still periodic scandals, but the sports world hadn’t fallen apart. At the same time, the Moneyball movement in baseball and beyond had pushed data and analytics into the mainstream, and fantasy sports had provided a soft entry point into sports betting for millions of people. The very idea of “public morals” now seemed antiquated; the national turn toward libertarianism bridged the gaping partisan divide between Republicans and Democrats. “There was so much more acceptance in general of gambling and risk taking,” Abarbanel says. “Part of that ties back to the moral element. … Now, we don’t necessarily view it as immoral. It still has sort of a sin industry stigma attached to it, but it’s generally not considered a moral fault.”

One of Brian Musburger’s clients during the pre-legalization era was Phil Jackson, then coaching the National Basketball Association’s Los Angeles Lakers, and one day, during a meeting with longtime Lakers owner Jerry Buss, Musburger found himself discussing the Las Vegas projected win totals for the Lakers during the coming season. And he thought to himself: This guy has a team of data scientists, but he’s looking to Vegas for his information?

“‘You Can Gamble Yourself into the Grave’: Is the U.S. Staring Down the Barrel of a Gambling Addiction Crisis?” by Patrick Hruby.

The legalization of gambling across the U.S. has set off record wagers, creating a generation in which many, especially younger men, are developing an unhealthy relationship to sports betting.

Start with smartphones. Sports gamblers who use mobile devices have higher rates of problem gambling than those who don’t. That’s no coincidence. Smartphones and their software are purposefully designed to hold our attention and keep us coming back for more. Wagering with virtual money or online credits is akin to betting with chips in a physical casino: It has a disinhibiting effect, which can result in larger and more frequent bets.

Most importantly, mobile technology means that sports gamblers can now wager all day, every day, on games and matches taking place across the planet. There are also more ways to bet than ever before, both before and during contests: on how many corner kicks will be taken in a soccer match, on whether three different teams will all cover the point spread, on whether the next serve in a live tennis match will be an ace or a fault.

The result? The traditional delay between risk and reward in sports gambling has been erased, replaced by a kind of digital slot machine. Research has linked this kind of rapid and impulsive gambling with increased addiction risk, and a 2018 study of regular sports bettors in Australia found that 78 percent of those who made wagers during live play could be classified as problem gamblers – compared to roughly 29 percent of those who didn’t make live bets.

“Most of my harm was through my phone,” says Pitcher, the podcast host in recovery. “It was just there all the time, and everything was so rapid – always on the move, hundreds of markets, always on your mind, going 100 miles per hour. You’re being sold cross-products and different promotions, too. And that is just lethal. Lethal.”

This has been Hreal Sports, a newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. If you have any questions or feedback, contact me at my website, www.patrickhruby.net. And if you enjoyed this, please sign up and share with your friends.