Global Sport Matters: The Return On Our Sports Investment Issue (Part I)

The stadium subsidy bottom line, playing hardball with team owners, how the U.S. gives sports special breaks, fan ownership in German soccer, and Nashville's chance to get more bang for its bucks.

Welcome to Hreal Sports, a newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. Sign up and tell your friends!

Welcome back! I’m delighted to share the first batch of stories for the June issue of Global Sport Matters, the digital publication of the Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University. For those of you who are unfamiliar with our work, we cover a wide range of outside the lines, sports and society topics though original research and reporting, and via podcasts, live events, standalone articles, and monthly themed issues.

Our latest issue is devoted to The Return On Our Sports Investment. From spending billions on sports stadiums to exempting leagues and organizations from pesky impediments such as antirust laws and OSHA, the United States invests an awful lot of public support into the private business of sports; in return, we generally receive solemn promises that our favorite teams won’t, like, move to Las Vegas. For now.

But how do fans and residents feel about this arrangement? What is the ideal role sports organizations should play in communities? Do these organizations owe the public more than they are giving? Should they be owned by the public in the first place?

To put things more succinctly: We, The People have been extremely generous. What should we expect in exchange?

Our issue attempts to provide answers—from economists and scholars who have studied these questions here and abroad, from reporters on location in Tennessee and Germany, and from an Arizona State University Global Sport Institute nationwide public opinion poll. Links and summaries are below for stories on the actual economic returns to communities of sports facility construction (SPOILER ALERT: tossing cash from the Joker’s Partyman float in Batman ‘89 would be about as effective), why the public would support timid politicians instead playing hardball with team owners, how the U.S. gives sports special breaks that go beyond building public housing for private teams, the upside-down world of fan ownership in German soccer, and Nashville's current opportunity to get more bang for its potential layout of some very big stadium construction bucks. Hope you enjoy—and stay tuned for Part II!

“Play Your Chips: U.S. Politicians Can and Should Demand More in Stadium Financing Deals,” by Patrick Hruby.

Yours truly has long argued that if cities, states, and politicians are going to give billionaire sports owners even more money via taxpayer contributions to corporate HQ construction, they should ask teams for way more than ephemeral promises to stay put. Guess what? A new ASU GSI public opinion poll suggests that the American public shares my views. I love being a tribune of the people!

Conducted in April in partnership with OH Predictive Insights, a market research and polling company based in Phoenix, the survey found that a minority of the public supports stadium subsidies, with 44 percent of respondents somewhat or strongly agreeing that state governments should provide funds to either build or maintain pro sports facilities, and 47 percent agreeing that local governments should do the same.

Add in the prospect of higher taxes—because, you know, $500 million doesn’t usually appear out of thin air—and that minority support plummets precipitously. Just 27 percent of respondents support raising taxes in general to pay for stadium financing, while less than one-third of respondents support raising taxes in the specific categories of sales, property, income, hotel, car rental, or food and beverages.

Of course, none of this reluctance to ante up this means that the public is wholly indifferent to sports—or to the prospect of gaining or losing a local pro team. Fifty-nine percent of respondents agree with the notion that the presence of such teams is a necessary element in a community’s identity, and 67 percent agree with the notion that said presence is an important part of a community’s economic health.

What these numbers suggest is that while the public isn’t keen to cut blank checks for bigger, shinier sports facilities, it does see value in having pro teams around, both as beacons of civic pride and businesses contributing to local prosperity. In turn, this means local politicians arguably have a tepid but defensible mandate to pursue stadium deals—provided they can produce a robust and demonstrable return on investment.

“So Your City Wants to Build a Stadium. Here’s What to Know,” by JC Bradbury.

Stadium negotiations in the U.S. can be filled with half-truths, exaggerated arguments, and promises about future local economic prosperity—Jobs! Development! A bigger tax base!—that wouldn’t be out of place in a Springfield Monorail sales presentation. But what do 30-plus years of actual economic study and analysis say? Your’e in luck: we asked an actual economist who studies and analyzes this stuff. Here's his handy guide to what anyone debating public financing for a stadium needs to know.

Stadium advocates often argue that stadium funding is a worthwhile public investment because game-related commerce improves local economic well-being by generating jobs, income, and tax revenue. But in reality, stadiums have a poor record of producing such benefits.

Economists Dennis Coates, Brad Humphreys, and I recently conducted a comprehensive review of more than 130 studies of the economic impact of sports teams and stadiums. Though the research methods, time periods, and stadiums examined vary, the findings are remarkably consistent: Teams and stadiums are not associated with having strong economic impacts on local communities. These findings explain why people in my line of work overwhelmingly agree that sports stadiums are poor public investments. In a recent University of Chicago survey of economic experts, 80 percent of respondents agreed that stadium subsidies were likely to cost taxpayers more than what they get in return.

As for the rosy economic projections conjured up to support stadium subsidies? They are doomed by design. Easy-to-observe spending on tickets, concessions, and other related consumption in and around stadiums comes largely from local residents who were already spending their income locally. A family that buys hot dogs, peanuts, and popcorn at the game would have otherwise spent that money at some other local business, perhaps going out to dinner or a movie. Stadiums don’t boost host economies, because stadium-related spending mostly isn’t new spending. It’s the same spending reallocated to a different location.

“Breaks of the Game: How the Government Subsidizes American Sports,” by Alex Kirshner.

Big budget bills aren't the only way governments in the U.S. subsidize sports organizations. Through antitrust and monopoly carve-outs, tax breaks, and other hard-to-see loopholes, the other breaks of the game are as varied as they are lucrative.

Some of the biggest government help for college sports comes from Washington, D.C., via the federal tax code. According to a 2009 Congressional Budget Office white paper titled "Tax Preferences for Collegiate Sports," about two-thirds of the athletic department revenue at large universities comes from ticket sales, television deals, merchandise licensing, and other activities that aren’t taxed by Uncle Sam. Why not tax that revenue? Historically, Congress and the Internal Revenue Service have ruled that college sports serve an educational purpose. The vast majority of American colleges enjoy 501(c)(3) status, which exempts most of a school’s earnings from federal income tax.

This includes most donations to a university – including those to its athletic department or booster organization, which may register under the same tax-exempt designation. Donor fundraising accounts for about 20 percent of athletic department revenue at Football Bowl Subdivision schools and slightly more in the top tier of the Power Five, according to a 2020 Knight Commission study. That works out to millions of dollars per year, per department.

A lot of that money arrives because alumni care about their schools and want to make sure their teams have nice stadiums, desirable amenities, and a budget to pay the best coaches. Getting a juicy tax break doesn’t hurt, though. For the high-dollar donors whose giving exceeds the Internal Revenue Service’s standard deduction ($12,550 in 2021), a dollar given to an athletic department can translate into one less dollar of income subject to federal tax – savings that climb well into the thousands or even millions of dollars.

“I think that’s really important, the ability to go to someone and say, ‘Hey, if you give us this money, it’ll help us build this thing at this place that you’re passionate about, and in addition, you’re going to get this tax deduction,’” says Mit Winter, a sports attorney at the Kansas City-based law firm Kennyhertz Perry. “That’s a pretty great selling point to get someone to donate money to something that they might already be inclined to donate to.”

“The Power and Fragility of German Soccer’s 50+1 Rule,” by Brian Blickenstaff.

In Germany, the Bundesliga operates under a long-held rule that requires 50 percent of a club plus one share to be possessed by team vereins—that is, fan clubs. The result of this people power? Lower prices for tickets and beer, deeper community ties, zero threats to move to Seattle, and a conspicuous lack of Dan Snyder. However, this tradition is not without its flaws. And it’s being challenged as more money flows into European soccer.

Almost every German soccer team is part of a sporting club known as a verein (pronounced fer-INE). According to a report from Germany’s Ministry of Sports Science, the average size of a German sporting club in 2018 was 267 people, but the biggest sports club is Bayern Munich, which has more than 290,000 members. A Bundesliga verein’s democratically elected leadership is responsible not just for maintaining huge budgets but also for organizing club events and offering members all manner of sporting opportunities beyond soccer. Eintracht’s members, for example, have more than 50 activities to choose from.

None of those activities are as popular or have a budget the size of the professional soccer team. If you know anything about European soccer, you know that team ownership can mirror that of pro sports in the United States, with big clubs often becoming the playthings of billionaires. Some of Europe’s top teams are owned by Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds, rich Americans, and, until recently, Russian oligarchs. This is not the case in Germany. In the bylaws of the German Football League – the DFL – there is a rule that the majority of every club must be owned by the club itself.

The rule, known colloquially as 50+1 (for 50 percent plus 1 share), is credited with creating an environment of fan engagement that has become a hallmark of German soccer – and the envy of fans in other leagues who feel voiceless in the face of private, often foreign, ownership. The perceived importance of the 50+1 rule is difficult to overstate. It has been studied in the Parliament of the United Kingdom as a model for a more sustainable approach to soccer. Florian Proeckl, a diehard Eintracht fan who traveled to Sevilla for the Europa League final, told me that “50+1 is the most important rule of German football and is a gatekeeper to the soul of the game.”

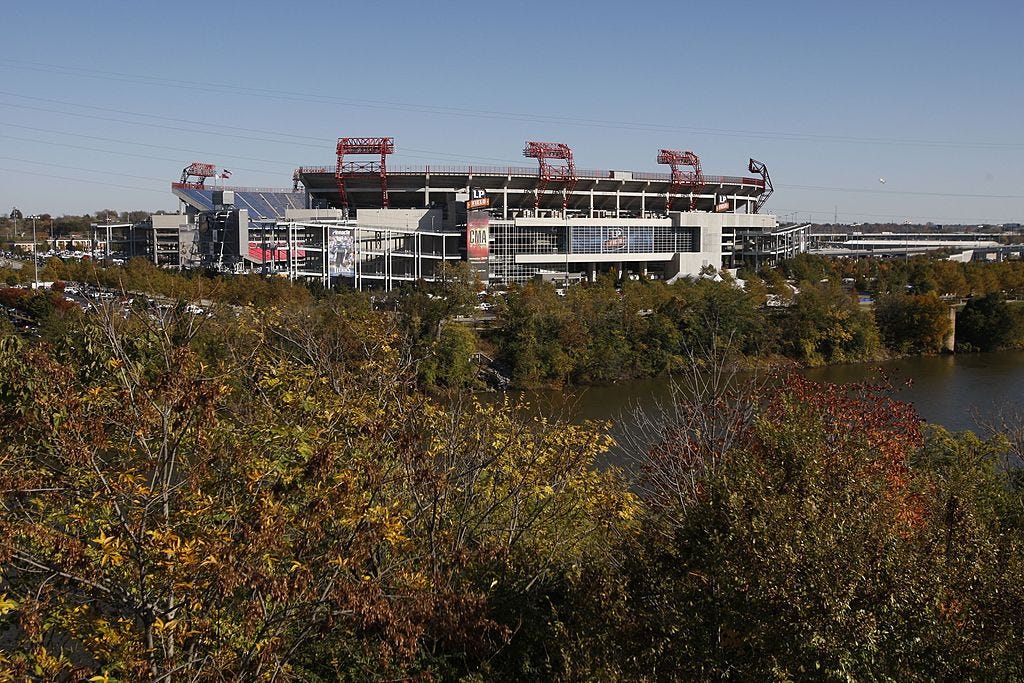

“More Bang for a Billion Bucks: Can Nashville Make a Better Sports Stadium Deal?” by Dan Fitzpatrick.

The Tennessee Titans are poised to collect a billion-dollar check from Nashville—in addition to $500 million from the state—toward the construction of a new stadium. Before finalizing an agreement, can the city negotiate a better return on its investment?

Maximizing return on investment does not exclusively mean revenues for the city. It also can come in the form of local jobs, workforce housing, pay standards, worker protections, and – in the case of the community around Nashville’s new soccer stadium – affordable childcare.

One way to achieve these kinds of goals is through a community benefits agreement (CBA), in which a private entity that represents local interests negotiates with a sports team to produce a stadium financing deal that includes measures designed to benefit the community directly.

Across the United States, CBAs have been a part of some stadium and surrounding development projects. In San Diego, a CBA was negotiated in 2005 for a development called Ballpark Village around a new stadium for Major League Baseball’s Padres. When the project finally broke ground in 2016, some benefits – including $20 million for 134 low-income apartments – already had been realized. And once construction was underway, the CBA guaranteed local hiring and made $750,000 available for pre-apprenticeship job training for disconnected youth and veterans.

In Pittsburgh, the CBA for a new arena for the National Hockey League’s Penguins also brought funding for neighborhood projects, including $2 million for a new grocery store. (That store ended up closing in 2019 after being open for five years, but a new grocery store is opening this summer at the same location.) In Milwaukee, the 2016 CBA for a new building for the National Basketball Association’s Bucks required the team’s owners to commit to higher wages for full-time jobs in a surrounding development – and just last month, Bucks owners promised to honor that commitment at new concert venues they are building adjacent to the arena.

This has been Hreal Sports, a newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. If you have any questions or feedback, contact me at my website, www.patrickhruby.net. And if you enjoyed this, please sign up and share with your friends.