Global Sport Matters: The Mental Health Issue (Part II)

Pro tennis isolation, abusive coaching, the toll of press conferences, post-sport identity crises, athletes creating help services, "middle-status athlete" anxiety, and more help needed in NCAA D-II.

Welcome to Hreal Sports, a newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. Sign up and tell your friends!

Welcome back! I’m delighted to share the second set of stories for the May issue of Global Sport Matters, the digital publication of the Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University. For those of you who are unfamiliar with our work, we cover a wide range of outside the lines, sports and society topics though original research and reporting, and via podcasts, live events, standalone articles, and monthly themed issues.

Our May issue is devoted to Mental Health. For a very long time, this topic was basically taboo within the hyper-competitive culture of sports. For athletes and others, acknowledging and admitting that you were, in fact, not okay mentally and emotionally was at best a sign of weakness—and at worst a threat to your livelihood. Organizations and fans alike were unsympathetic toward and unequipped to deal with the very real mental health challenges faced by many within sports, creating stigma, silence, and isolation that exacerbated those issues.

Fortunately, times are changing. Sports are beginning to reckon with mental health in a positive and constructive way, as athletes speak out and teams and leagues understand that they can and should do more to support them. Links and summaries are below for stories on isolation in professional tennis, abusive coaching, the psychological toll of press conferences, post-playing identity crises in college sports, athletes creating help services, "middle-status athlete" anxiety, and more help needed in NCAA Division II. Hope you enjoy—and if you missed Part I, you can catch up by clicking here.

“The Other Opponent: The Mental Health Challenges of Professional Tennis,” by Brittany Collens.

In this first-person piece, a professional tennis player opens up about the stress, anxiety, and bouts of self-doubt that are part of her life—and how they overlap with the physical toll of traveling the globe and finding places to compete week to week.

On this day, however, I’m finally returning home after one month of being on the road. Coming home brings on so many emotions, making players like myself hyper-aware of the instability that professional tennis can bring. It’s a reminder that even your closest friends and family can’t fully understand your life and experiences. It means realizing that the world you leave in order to chase ranking points continues on without you – and that while you’re gone, you’re missing out on important events and moments.

Every time I come home, my nieces and nephews are impossibly bigger. When I’m traveling, I sometimes avoid FaceTiming my family on Friday evenings – because I know they are all out to dinner. They call me anyway. I put on a smile for them, even though I’m sad that I can’t be at my favorite restaurant, too. I snap myself into being present, focused on where I am and what I’m doing. Daydreaming can make me homesick, so it’s better not to.

When talking to the people closest to me – or anyone, really – I constantly remind myself to not sound ungrateful. As a professional athlete, I don’t work a traditional 9-to-5 job. In many ways, I’m fortunate. But at the same time, trying to make it in my sport is anything but glamorous. Tennis pros have a need to be understood when expressing how lonely, how unrelatable, and, for players ranked outside the top 250 or so, just how scrappy our lives are. And that need is often unmet.

“‘A Mental Health Battle’: How Abusive Coaching Impacts College Athletes,” by Katie Lever.

A former college athlete turned sports scholar explains why abusive coaching is so commonplace in college sports, how it affects athletes, and what can be done to curb it.

For college athletes, abusive coaching can exacerbate existing feelings of insecurity, anxiety, and depression. For Ramirez, this manifested in increased self-criticism on and off the field, as well as heightened anxiety. The question “what’s wrong with me?” ran through her head daily.

Hazlett said that the same effect is common in abusive relationships between intimate partners, “even though the relationship might look very different.” These relationships are characterized by “very high levels of control” and have wide-ranging, damaging mental health effects on victims that can persist long after the relationship ends.

“Anxiety, depression suicidal thoughts, all those things,” Simpson said. “You’ll often see an athlete excluding themselves from society or feeling really low self-esteem and cognitive functioning.”

Because abusers often use isolation tactics, there can be social consequences for athletes that leave them feeling alone and cut off from others – even after they graduate. “Oftentimes, those abusive relationships have led them to maybe cut off people in their family or relationships that were protective to them,” Simpson said. “That can put them in situations where they're actually unsafe outside of their sport as well and become victims and other areas of society.”

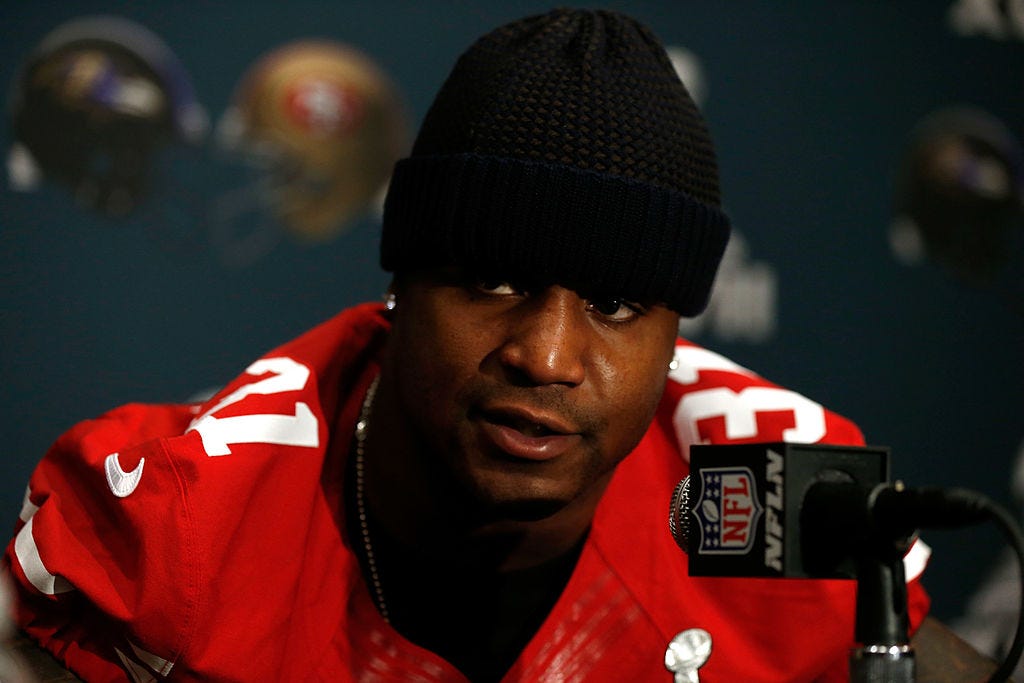

“What Is Sports Media's Role When It Comes to Mental Health?” by Brian Moritz.

As athletes take a stand for their mental wellbeing, many have pointed to media interactions and news conferences as the cause of increased stress and anxiety.

The easy answer would be to get rid of news conferences. After all, if reporters don’t like them and players don’t need them, then what’s the point? Especially when they create the unavoidable power dynamics of a group of largely older white men interrogating young women or younger black athletes who grew up around violence and poverty.

“We are not the good guys here,” Jonathan Liew wrote in The Guardian in 2021. “We are no longer the power. And one of the world’s best athletes would literally rather quit a Grand Slam tournament than have to talk to the press. Rather than scrutinizing what that says about her, it might be worth asking what that says about us.”

But the reporters and former athletes interviewed for this article didn’t feel doing away with news conferences was realistic. Blake said that he was concerned that some players who view news conferences as a nuisance would start using mental health as an excuse to duck their obligations.

There’s also the problem of scale. Think of Super Bowl media week. Imagine a world where, instead of one big press conference, athletes like Tom Brady or Matthew Stafford have to do hundreds of individual interviews. That might be more stressful, not less.

Additionally, the millions and billions of dollars in the sports world exist at least in part due to media coverage. Many athletes can blast their stories and perspectives to millions as a result of reporter interactions. Sports have been a pillar of the attention economy long before anyone was using the term attention economy.

“After Sport, a College Athlete’s Identity Loss Can Harm their Mental Health,” by Victor Kidd.

A former college football player turned social worker and psychotherapist explains how the transition from school to the working world can bring an identity crisis and mental health trouble for college athletes whose lives have been built around their sports prowess.

It was a brisk November night. As I left the Virginia State University football stadium for the last time after turning in my equipment, Kendrick Lamar’s “Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst” played in my headphones, and I looked back at the gate. Tears rolled down my face. Fifteen years of my existence – sweating and striving with a feeling of purpose, building friendships and a sense of identity, all while playing a sport that I deeply loved – would soon fade away. I wondered: who was I, now? And what would I do next?

I grew up dreaming of playing college football. When I got the chance to play linebacker for Virginia State, a historically black Division II school in central Virginia, the experience did not disappoint. From hearing the Trojan Explosion marching band hype up the crowd during hot afternoons in Rogers Stadium to attending postgame parties with Big Blue teammates who were like brothers, my time as an athlete was, in a word, intoxicating.

I got to play in a Colonial Intercollegiate Athletic Association (CIAA) championship game, my final game with the program, which I closed out with the game-winning tackle. Yet the most emotional moment of my football career came at the very end as I left the stadium for that final time.

My grieving process had begun.

“‘Relatability is Key’: Athletes Are Taking Control of the Business of Mental Health,” by Allison Torres Burtka.

Athletes at all levels, from youth to pros, struggle with mental health. But barriers often get in the way of getting the resources they need. Numerous former athletes have taken ownership of the problem.

As a basketball player at Missouri State University, Nafis Ricks was where he wanted to be. He’d achieved his goal of earning a scholarship, and he was playing the game he loved. But he was carrying the trauma of his brother being killed a few years earlier, and at college, the pressures of being a Division I student-athlete started to mount. He had a mental health breakdown and asked his coach for help, which led to an appointment with a psychologist.

“It helped me in a dramatic way, not just in sports, but in my life,” he says. “What I got out of therapy is I got to dig deep inside myself, and look myself in the mirror and understand that I’m not the only one going through struggles. It’s OK not to be OK sometimes.”

Today, Ricks has a master’s in psychology and is working toward his doctorate in counseling psychology. He created Collaboration Management, which provides mental health services to athletes. It serves as a mental health coaching hub, providing one-on-one and group coaching as well as other resources. Ricks hosts online seminars and workshops, sometimes bringing in a therapist or psychologist. “It creates a safe space for athletes to talk about the things that they’re going through,” he says.

As mental health has become a larger focus among athletes, many former collegiate and pro athletes like Ricks have made it their profession, launching startups to better connect athletes with mental health resources and treatment.

“Supporting ‘Middle-Status Athletes’ Starts with Understanding, Development and Clarity,” by Scott N. Brooks.

Not every young athlete can be neatly sorted into bench warmer or superstar. Some fall in the middle, and they carry unique needs and can pose specific challenges for coaches.

Middle-status players have limited opportunities. In competitive settings, not everyone will be treated the same as star players. Some athletes have to sit and watch from the sidelines, waiting to get in the game. Those who aren’t starters or considered “go-to” players have to manage uncertainty – not knowing how much they’ll play from game to game, not knowing if they will be subbed back into a game after being taken out, and knowing that playing time and being a star is not always a simple meritocracy. These players do not control their fates.

Middle-status players are essentially stuck in traffic, with someone ahead of them. Maybe they have to split playing time, or maybe the coach doesn’t want them to score or try to do too much. For middle-status players, something has to happen to the star players in order to open opportunities for more playing time and the freedom to make mistakes.

If someone has ambitions of being a “known” athlete, one with a positive reputation who is considered vital to a team’s success and acknowledged by others, then being middle-status is a detour, even an off-ramp. Middle status is a constraint that determines how much you play, what is expected and not expected of you when you do play, and the extent to which you are allowed to take chances and play through errors.

In youth sport, middle status can be acceptable or unacceptable to a young athlete, depending on their ambition. A kid who wants or believes they deserve star treatment – that their entire future is dependent upon being a star in the present – is going to find it harder to manage competitive stress than a kid who believes that sports are about personal growth and being part of something bigger than themselves.

“Division II Athletic Departments Can't Support Athlete Mental Health Without More Resources,” by Rebecca Falkner.

It's one thing for big-time Power 5 football players to find mental health help on campus, but in smaller Division II or III athletic programs, funding and staffing are in short supply.

I surveyed 174 college athletes for my thesis survey and asked questions relating to my university, university services, and their time as athletes. In my research, the results stated that 143 athletes felt like their performance had been hindered at least once a week due to mental health. In other words, 82 percent felt they could not perform their best due to mental health. What happens if a bad mental health day takes place during the game or match of the year? What happens if athletes decide that they have had too many of those days and have suicidal ideations? What happens next?

Friends of mine who played at mid-major Division I universities had access to sports psychologists and could see one whenever they needed. But Division II and III schools generally don’t have comparable funding and resources. According to the NCAA, median athletic expenses for Divisions II and III in 2021-22 were $6.8 million and $2.4-4.4 million, respectively, while for Division I schools in 2020 that number was anywhere from $17 million to $120 million.

Many universities offer free counseling and other similar services to the general student body. But most of those counselors and psychologists do not have training in the sports component that college athletes seek. I have worked with therapists before who were amazing, but when I asked for performance-specific advice and guidance, they did not know where to even begin. At my university, counselors had expertise in different areas, but none had a sports emphasis.

This has been Hreal Sports, a newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. If you have any questions or feedback, contact me at my website, www.patrickhruby.net. And if you enjoyed this, please sign up and share with your friends.