Global Sport Matters: The College Sports 2.0 Issue (Part I)

How college sports can thrive without the NCAA, unionizing athletes, building the business of women's basketball, making football brain safe(r), and diversifying sports leadership.

Welcome to Hreal Sports, a newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. Sign up and tell your friends!

Hello again! I’m thrilled to share the first batch of stories for the latest issue of Global Sport Matters, the digital publication of the Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University. As I’ve mentioned before, we cover a wide range of outside the lines, sports and society topics though original research and reporting, and via podcasts, live events, standalone articles, and monthly themed issues.

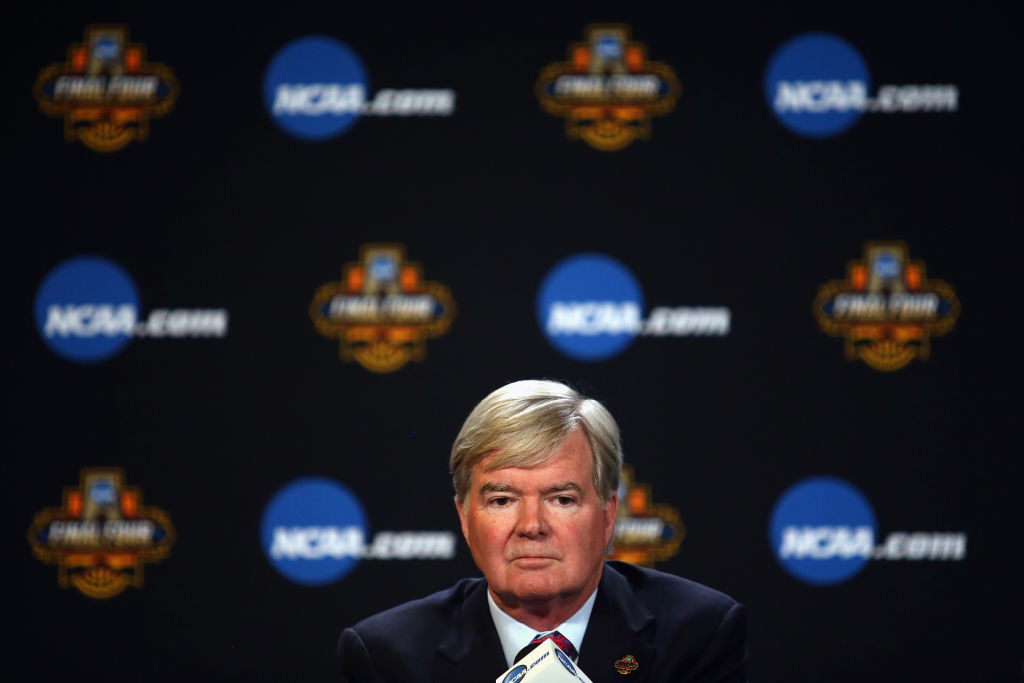

Our March issue is on College Sports 2.0. Last summer, National Collegiate Athletic Association president Mark Emmert openly acknowledged it was “the right time” to ask the question “if we were going to build college sports again, and in 2020 instead of 1920, what would that look like?”

Our issue is devoted to answers. Links and summaries are below for stories on how college sports can thrive without the NCAA, unionizing athletes, building the business of women's basketball, making football brain safe(r), and diversifying sports leadership. Hope you enjoy!

“‘A Rethinking of Sports Governance at the Highest Level’: How College Sports Can Thrive Without the NCAA,” by Victoria Jackson.

It may seem daunting to imagine a U.S. college sports world that does not include the NCAA, but advocates around the industry believe the separation of Olympic development and university-sponsored sports would be a helpful start toward a more sensible system.

Rocky Harris is uniquely positioned to understand the relationship between professional football, college football, and Olympic sports in the U.S. He has worked for the 49ers and the Texans in the NFL in addition to being COO of the Arizona State athletics department. Now, he is the CEO of USA Triathlon, an Olympic NGB. These experiences allow Harris to see the macro issues facing American sport.

When I wrote a story last summer about how American college football players pay for the world’s Olympic development thanks to “collegiate amateurism,” Harris called me up to remind me that the NFL is getting off scot-free and deserves some of the criticism here. The NFL enjoys streamlined scouting and player-development services from college football, which Harris sees as a minor league system. “They need to start funding some of this, too,” he says. But, generally, Harris believes that at the institutional level, the preoccupation with money and how it is used has distorted the mission of college sports, shifting it from serving athletes to serving revenue generation. Harris explains that this means athletes are not being well-served by a system that appears hopelessly broken to those inside it.

“College sports claims a mission and does the opposite,” Harris said. “And when college sports leaders consistently show they are not in line with what they say their mission is, they lose the public’s trust.”

Asked if a sport-by-sport restructuring could be a more optimal model than the patchwork approach we have now, Harris excitedly explained that “over the last 50 years, a lot has changed and policies haven’t shifted fast enough. Assuming we separate out football, and maybe also men’s and women’s basketball, what we could be doing is designing with a sport-specific focus through sport verticals, perhaps under a USOPC with an expanded mission, and with an NCAA as one part of that system, and each college sports space organized within the sports vertical.”

Harris continued: “We need a rethinking of sports governance at the highest level. Everyone sees how inefficient this is. It is not sustainable.”

“Why a College Athlete Union Seems Inevitable – and How it Could Work,” by Alex Kirshner.

As college athletes score wins in court and the business of NCAA football grows, labor experts believe a college athlete union could come soon, and are directing their energy toward making that union as effective as possible.

Once unions arrive in college sports — whether sport by sport, school by school, conference by conference, national, or some sort of mix — their work will be cut out for them. Every union faces similar internal and external challenges, including keeping members unified on the road to a contract, making decisions about where to spend political capital, and bargaining with management. Negotiating a first contract makes everything harder, not just because of inexperience but also because there isn’t much of a template to follow. In an industry with no union history at all, college athletes will be starting from scratch. (From 2017 to 2020, I was on the organizing and bargaining committees for a new union at my old employer, Vox Media.)

That said, the initial college athlete unions likely will have an opportunity to be effective, and effective quickly, for their members. Nearly seven in 10 Americans currently approve of unions, the highest rate in decades. Much of the public believes that athletes should be paid. (That belief is much more prevalent among Democrats than Republicans). Meanwhile, college athletes have millions of devoted fans and are the essential workers in a wildly popular entertainment product. Add that up and an athlete union could have a strong wind of public support at its back, one that would place additional pressure on universities to make favorable deals. Moreover, the past few years have seen a breakthrough in college athletes using their own platforms and media savvy to influence their schools. Similar dynamics could play into a union’s hands.

Moreover, unions succeed when they stick together and struggle when they don’t. College athletes live together and spend their days together, often taking the same classes and hanging out even when they’re not playing, practicing, or training. Their coaches drill into them the importance of supporting their teammates. That cohesion could help an athlete union build power.

At the actual bargaining table, the many obvious and ongoing problems within college sports would give athlete unions plenty of things to fight for. They might ask for salaries, or more generous scholarships, or more time to complete their degrees, or less demanding practice and workout schedules, or more freedom to pursue majors that conflict with athletic demands.

“For the NCAA, Building the Business of Women’s Sports Starts With Basketball,” by David Berri.

Sports fans were outraged at how last year's NCAA women's basketball tournament was given short shrift compared with the men's tourney. Here's how the NCAA can undo its worst instincts and grow women's basketball as a business.

Imagine, for a minute, that college sports are stocks. Football and men’s basketball are essentially Pepsi and Coca-Cola. Both are very popular. Both make lots of money. Both have been around for decades. But their potential for growth is limited. Their markets are mature and saturated; they are well-known and well-sampled; very few people who aren’t already fans of them are going to become cola drinkers in the future.

By contrast, women’s basketball (like most women’s sports) is arguably a growth stock. It’s a younger, less established product. It hasn’t been consistently promoted or marketed. It likely has many more future fans to convert. A concerted effort to invest in women’s basketball over time – not as an afterthought or a begrudging corporate charity project, but as part of an aggressive growth strategy – could yield impressive returns for the NCAA and its schools.

Consider the early spending on college athlete name, image, and likeness (NIL) deals. The majority of it has gone toward men. However, that’s due to the popularity of football. According to Jim Cavale, the CEO of INFLCR, an online marketing platform for athletes, “if you remove football from the equation, transactions or activities disclosed by female student-athletes make up more than 50 percent of the total for all other sports.”

Based on data from INFLCR and Opendorse, another online NIL platform, five women’s sports rank in the top 10 for NIL activities: track and field, volleyball, basketball, soccer, and softball. Opendorse also reports that six women's sports are also in the top 10 for NIL compensation, led by women’s basketball – which at 26.2 percent trails football (45.7 percent) but is actually ahead of men’s basketball (18 percent).

“We Don’t Have to Get Rid of College Football to Make It Brain-Safe(r),” by Chris Nowinski.

The NCAA does not have a uniform policy for member schools' football programs regarding brain trauma and concussions. But there are easy, manageable steps that could be taken in college football to make the game safer for athletes' brains.

The NCAA’s own research reveals that 72 percent of football concussions and 67 percent of total head impact exposures come in practice. The math on this is simple: Less exposure means less risk of injury and disease.

Other levels of football are showing that this can work. The NFL allows a maximum of 14 full-contact practices during its 17-week regular season – and those practices account for only 18 percent of the league’s documented concussions. In 2014, the Michigan High School Athletic Association instituted contact practice limits that resulted in one high school football team suffering 53 percent fewer head impacts in practice. A 2019 rule change reduced contact in Michigan from 90 minutes allowed per week to 30 minutes. New Jersey is now down to 15 minutes of contact per week.

But colleges simply have not done enough, and coaches bear much of the responsibility for that. By widely ignoring practice changes at the NFL level, they have been remarkably persistent in finding ways to expose their players to head impacts. Case in point? In 2017, the NCAA banned two-a-day football practices during the preseason with the goal of reducing RHI exposure for football players. When the effect of rule change was formally studied, it turned out it had the reverse effect: Coaches crammed 26 percent more head impacts into one practice than they had in prior years in two practices. In addition to rebelling against the spirit of the rule change, they found a way to make practices more dangerous!

Some college coaches have been outspoken about their lack of concern about CTE. Larry Fedora, the head football coach at the University of North Carolina, said in 2018 that “I don’t think it’s been proven that the game of football causes CTE. We don’t really know that. Are there chances for concussions? Of course. There are collisions. But the game is safer than it’s ever been.”

On the other end of the spectrum, Dartmouth University head coach Buddy Teevens has received positive national media attention for his commitment to ensuring that his players “will never tackle a teammate.” Despite banning live tackling in practice, Dartmouth has won the Ivy League and gone 9-1 in each of the past two seasons, and the defense gave up the fewest points in the league in 2021. Sadly, no major college coach is trying to replicate Teevens’ coaching methods. And while Ivy League coaches in 2016 voted unanimously to eliminate full-contact practices during the season, no other conference has followed suit.

“A New NCAA Constitution Centered On Diversity? Here’s Where To Start,” by Kenneth Shropshire.

NCAA President Mark Emmert recently indicated the association’s new charter ought to focus heavily on diversity, equity and inclusion. But while recent college sports trends lend to optimism the body can achieve this, it currently is no better than the numerous other U.S. sports with a heavy race and gender imbalance.

Many powerful people across college sports—including school athletic directors, university presidents, conference commissioners, and National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) president Mark Emmert—have publicly acknowledged a need for more equitable hiring practices and outcomes. Yet those same people have not, as a group, made significantly more diverse hiring decisions. Progress has been slow and challenging, and in most cases, the new bosses look a lot like the old ones.

As is the case with other sports entities, the diversity of the athletes in college sports creates expectation for leadership that is also diverse. Is there a better path to that? Everyone who cares about this topic assumes one exists, but no one has figured out exactly what it is.

In truth, the best route to more diverse leadership is most likely not a single strategy, but rather a combination of them.

College sports are in a revolutionary moment. Old shibboleths, particularly the ones around amateurism, are being discarded. The NCAA is reexamining some of its fundamental ways of doing business. Lawmakers and litigators alike are forcing change. Conversations about economic, social, and racial injustice that were once on the margins of the enterprise have moved to the center.

This shift is creating room for experimentation: college athletes are now free to profit from their names, images, and likenesses, and also more free to transfer among schools. Perhaps this spirit of trying new things can inform leadership diversity efforts, too.

This has been Hreal Sports, a newsletter written by Patrick Hruby about sports things that don’t stick to sports. If you have any questions or feedback, contact me at my website, www.patrickhruby.net. And if you enjoyed this, please sign up and share with your friends.